15. TRC & Employment

Robline Davey

Introduction

Depending on your context, you may discover that you are already familiar with the information in this chapter. For some, it may be brand new. Whether you are an international student in Canada, a domestic student, or an Indigenous student, it is important to educate or remind us of the difficult history experienced by Indigenous peoples in Canada because it has led to the current employment context today. This chapter aims to describe the Canadian employment context as it relates to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s (TRC, 2015a) Calls to Action (CTA), specifically CTA 92 which can be summarized by calling for reconciliation in the workplace, including improved intercultural skills for employees and administration.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapters, you should be able to:

- Locate and list government policies, initiatives, and institutions that have historically and currently oppressed Indigenous Peoples, resulting in the current employment context in Canada. (Land acknowledgement)

- Describe the impact colonialism has had on Indigenous communities, and detail how that has caused a lower representation of and/or increased barriers for Indigenous Peoples in various employment sectors. (Land acknowledgement)

- Explain the significance of rights-based documents, such as the TRC’s Calls to Action or UNDRIP, and articulate the impact that adopting these principles has in an employment context or potential workplace environment. (Land acknowledgement)

- Develop several strategies to support reconciliation within a prospective workplace. (Land acknowledgement)

Who Are the Indigenous Peoples of Canada?

Indigenous Peoples make up 4.9% of the total Canadian population (Statistics Canada, 2018a). A long history of colonialism, genocide, and racism has led to inequities in many areas of life for Indigenous Peoples living in Canada. The term “Indigenous” is an overarching term that refers to the three legally recognized groups who lived in Canada before it was colonized by settlers: First Nations, Inuit, and Métis (see Table 15.1). These three groups are legally recognized as “Aboriginal” in Section 35(2) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982) in the Constitution Act, 1982.

Current State of Employment for Indigenous Canadians

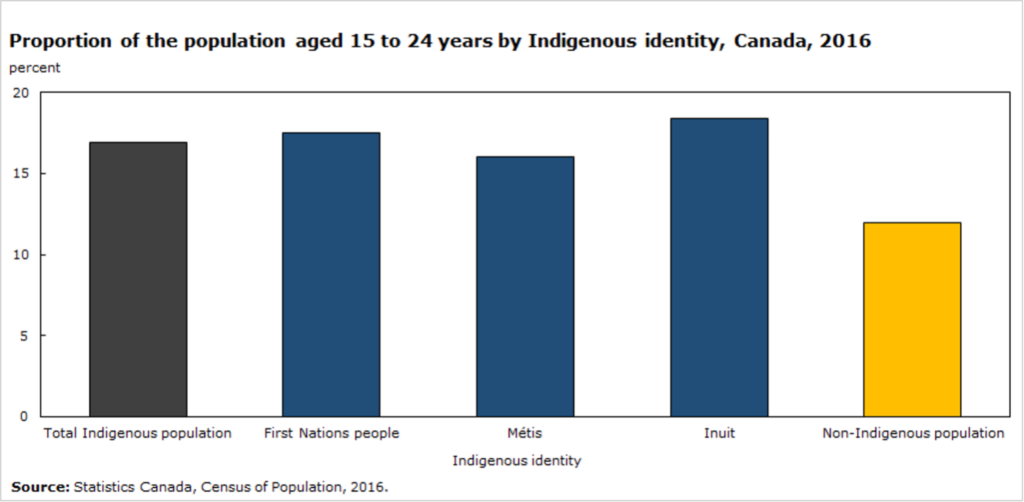

Indigenous Peoples are the fastest-growing segment of the population, and those aged 25 to 39 will be a significant percentage of the workforce in the coming years (see Figure 15.1). Statistics Canada (2012) reported that 46.2% of the Indigenous population was younger than 24 years old, compared to only 30% of the non-Indigenous population. That number has not changed much since then. In 2020, 44% of those identifying as Indigenous were younger than 25 years old (Statistics Canada, 2020). Yet according to a report by Catalyst, Indigenous Peoples are underrepresented in the employment sector, are impacted by a wage gap, and may experience isolation due to a lack of Indigenous role models in organizations (Thorpe-Moscon et al., 2021; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2018). Using data from Statistics Canada, it is reported that the unemployment rate for the Indigenous population was 9.8% in 2024 (Statistics Canada, 2025), slightly more for men and slightly less for women.

Indigenous employees are under-represented in many fields, including finance, consulting, law, banking, and financial institutions (Deschamps, 2021; Canadian Human Rights Commission [CHRC], 2020). The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC, 2015b) observed that disparities in education and skills were closely tied to these employment outcomes. Educational attainment and employment rates are positively correlated; those with the lowest levels of educational attainment will also experience the lowest levels of employment rates (OECD, 2018). This correlation should mean that Indigenous Peoples engaged in post-secondary education are more likely to find employment.

Yet in her dissertation, Overmars (2019) indicates that looking only at educational attainment is an oversimplification, emphasizing that colonization has played a role in lower rates of employment participation. The researcher also cites a lack of culturally appropriate workplaces and values misalignment, which may contribute to lower rates of employment or employee well-being. For more information on demographics and statistics, visit Statistics Canada (2017b). The graph in Figure 15.1 from Statistics Canada (2021) illustrates the high percentage of Indigenous youth compared to non-Indigenous Canadians.

The Indigenous Skills and Employment Training (ISET) program (Employment and Social Development Canada [ESDC], 2023) is an initiative by the federal government in partnership with Indigenous organizations. This program aims to close the gap in educational and employment outcomes. ISET increases access to post-secondary education for Indigenous Peoples and supports those seeking employment and career pathways for Indigenous workers. The program offers “job-finding skills and training, wage subsidies to encourage employers to hire Indigenous workers, financial subsidies to help individuals access employment or obtain skills for employment, entrepreneurial skills development supports to help with returning to school, and childcare for parents in training” (OECD, 2018).

Microaggressions in the Workplace

In fact, 60% of Indigenous employees surveyed in Canada described feeling emotionally unsafe at work (Deschamps, 2021). Your colleagues, even in mainstream organizations, may not understand the history, cultures, or burdens that Indigenous Peoples carry (Julien et al., 2017); this can lead to microaggressions, myths, and misconceptions about Indigenous Peoples (Deloitte, 2012). For example, Indigenous individuals are often questioned about the notion that they do not pay income taxes (Joseph, 2018). However, Section 87 of the Indian Act (1985) states that the “personal property of an Indian or a band situated on a reserve” is tax-exempt, as is income earned from employment on a reserve. The majority of Indigenous workers live or work off-reserve, so they pay the same taxes as other Canadians. Inuit and Métis people are not eligible for this exemption, as they generally do not live on reserves (Joseph, 2018).

A particularly good resource to counter common myths is Bob Joseph’s (2021) free e-book Dispelling Common Myths About Indigenous Peoples: 9 Myths and Realities. You can read more about this at the Indigenous Corporate Training website, and the Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples blog in the post “Insight on 10 Myths About Indigenous Peoples” (Joseph, 2018).

How to Be an Ally to Indigenous Peoples

For our purposes, this chapter focuses on what actions colleagues can take to become allies in an employment context. Regardless of your level of understanding of the differences in worldviews and cultures of Indigenous Peoples, reflecting upon your biases and assumptions is an excellent starting place in terms of understanding unexamined beliefs about Indigenous cultures. Taking steps to understand Indigenous values, and specifically, the values of your Indigenous colleagues is important. Several online courses support professional development and provide an increased understanding of the various and different worldviews of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

Online Professional Development Course Examples

Two robust resources are the following online courses (MOOCs) developed and delivered by the University of British Columbia (UBC) and the University of Alberta (UofA). Unless you desire a certificate of completion, both are free. They are self-paced asynchronous modules, so you can learn at your own pace.

- Reconciliation Through Indigenous Education (UBC, n.d.): A 6-week online course.

- Indigenous Canada (UofA, n.d.): A 12-week online course. UofA students can receive credit for the course.

Education and competency training can foster understanding, relationships, and work environments that support Indigenous employees’ sense of belonging and contribute to their ability to thrive in the workplace. Make it a priority to learn about local Indigenous cultures where you live and work. Acknowledge the diversity among First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples, and learn about your colleagues. Look for ways to learn about Indigenous values, and specifically seek out information about the values of communities in your area. For example, at Thompson Rivers University, many students are Secwépemc and from the communities around Secwepemc’uluw. Understand that Indigenous Peoples are not a homogeneous group, despite the fact that many Indigenous cultures share values and belief systems.

Exercise 15.1

Locate the Traditional Indigenous Territory Where You Live or Work

Do research to find out more about the Indigenous Peoples whose land you work or live on. The following maps can be used to locate the territory you are on and learn more about treaties, treaty work in progress, and languages spoken in each area.

- First Peoples’ Map of BC (First Peoples Cultural Council, n.d.)

- BC Treaty Commission (n.d.) interactive map: Offers more about the status of treaty negotiations.

- Native Land Interactive Map (Native Land Digital, n.d.): Can be used to search and filter by treaty, language, and ancestral territory from a global perspective.

Next, you can use your research to answer the following questions:

If you are using a printed copy, you can scan the QR code with your digital device to go directly to Exercise 15.1 Locate the Traditional Indigenous Territory Where You Live or Work

Further Reading

To learn more about Indigenous cultures in Canada, explore the following resources (also see Appendix N: Resources to Increase Your Knowledge About Indigenous Peoples):

- Indigenous Canada: A free, online course at the UofA (n.d.)

- Reconciliation Through Indigenous Education: A free, online course at UBC (n.d.)

- Indigenous Foundations: An information resource by UBC (First Nations & Indigenous Studies, 2009)

Barriers & Obstacles to Employment

A number of barriers disproportionately impact Indigenous Peoples in accessing stable employment and economic stability. Many of these obstacles are rooted in historical racism and have resulted in existing societal circumstances which prevent equitable access to economic stability. Eight barriers are listed by Bob Joseph (2019) in his blog post: “8 Basic Barriers to Indigenous Employment”. These same barriers existed 20 years ago and have not significantly changed.

Many government assimilation laws and policies—such as the residential school system, Sixties Scoop, and Indian Act policies—created conditions in which intergenerational trauma combined with discriminatory practices and laws. This combination caused a lack of access to standard services that the average Canadian has access to. For example, poverty, poor health, and lower-than-average education levels have resulted from these systems. We must also include the lack of clean drinking water and less access to completing high school education in remote locations.

Other barriers and obstacles to employment for Indigenous Peoples include:

- Poverty and poor housing

- Literacy and education

- Cultural differences

- Racism, discrimination, and stereotypes

- Self-esteem

- Driving licences

- Transportation

- Child care

Because higher levels of numeracy and literacy have been correlated with increased labour force participation (Arriagado & Hango, 2016), it is important to create opportunities to increase these levels for Indigenous Peoples. For the many reasons listed above, literacy and numeracy levels have been historically lower for Indigenous Peoples than for the general population of Canada. Because of the documented lower educational levels, Indigenous Peoples may be impacted negatively and may be more vulnerable to shifts in the economy. Cultural differences between employers and colleagues can influence the extent to which mutual respectful relationships are built, which is integral for a safe workplace environment. Similarly, racism, discrimination, stereotypes, and bias all influence our worldviews and how we view our colleagues.

Various myths are perpetuated about the perceived benefits that Indigenous Peoples are entitled to in Canada. One particular myth that continues is that Indigenous Peoples are perceived as having special treatment. While this is not true, in the current employment context, there are numerous Indigenous employment pathways that have developed as a result of the TRC’s (2015a) Calls to Action report, with organizations specifically seeking Indigenous applicants. Recently, a shift towards EDI has resulted in interest and a legal requirement to diversify the employment sector. In fact, there is sufficient evidence to support the notion that diversity in all areas of decision-making results in more equitable policies for Canadians (Rao & Tilt, 2015). Ensure that you self-identify in support of any application, even if not specifically as Indigenous, and view yourself from a strengths-based place because your voice and perspectives are important and highly sought after in many sectors. Healthy self-esteem is a key factor in presenting oneself well in interviews.

It is important to note that Indigenous Peoples often feel that they need to leave their Indigenous identity and culture at the door when entering and engaging in non-Indigenous spaces. Corporate culture is definitely a specific environment requiring various communication skills and styles. It can be helpful to develop the skill set required for communicating in the workplace and recognizing the dominant corporate culture. For example, is it relaxed, or formal? What types of communication do employees use?

For those of us who are new to a certain sector or workplace, it can feel like we are taking on a different identity. This feeling is common. It may be that you have various identities—a professional identity that you switch to at work and various other social identities that you switch to for connecting with friends or family. People refer to this as code-switching. Indigenous peoples may be impacted by this more than non-Indigenous employees, due to the fact that the worldviews we espouse can be very different than colleagues or the organization itself.

The ability to navigate various cultures is an advantage and may allow you to bring your Indigenous or your unique cultural perspective to your chosen organization. For example, adjusting how we communicate in the workplace can be helpful for meetings, championing ideas, and promoting oneself. That said, employers are advised to create new spaces and processes in the workplace culture that are inclusive, so that other perspectives are more easily recognized without employees being required to adjust to workplace culture.

For this reason, many Indigenous Peoples—whether students or employees—may develop multiple ways of communicating, depending on what context they find themselves in. In one environment, we may communicate in ways that are culturally grounded, but in non-Indigenous spaces, we may develop an identity that is more congruent with the implicit or explicit values of the non-Indigenous space. The term code-switching is often used to describe the ways in which individuals adapt ways of relating and communicating with others in various and different spaces such as school, community, family, employment contexts, and social spaces. Code-switching can be cognitively tiring; it can be mentally taxing to continually change your communication style to adapt to cultural contexts that differ from your culture of origin. This experience is common among Black, Indigenous, and people-of-colour (BIPOC) individuals.

It is worth reflecting upon communication styles, considering this as a factor in decision-making regarding where you see yourself working. Various communication styles are often required but are not always explicitly described by organizations. Adapting to a corporate culture may require an employee to adopt specific ways of communicating that are recognized in the organization but may be different than what we are used to using in other environments.

Some challenges Indigenous Peoples face in terms of employment include issues of isolation, especially those who transition from remote areas and have to become accustomed to a new city or urban culture. Additional challenges include developing ways to adapt to new cultural norms, such as workplace culture, and navigating institutions that are predominantly based on Western values. A lack of role models in senior positions can contribute to low retention and recruitment. As Deloitte (2012) reported, retention is impacted by the lack of familiar faces. Not seeing ourselves in the company impacts our sense of belonging. One way to support employees who find themselves in this situation is to develop mentorship programs and create support systems for Indigenous employees.

Not possessing a driver’s license can also be a barrier to employment opportunities. It is often a requirement of employment, and the ability to drive can be necessary to transport you to an interview, your workplace, or to testing centres, which are often part of an application process depending on the type of employment you are looking for. Remote communities seldom have reliable public transportation, and it can be difficult to find an automobile in remote communities to learn how to drive or to take the license road test. The high cost of insurance for younger people, who are just starting out, is another barrier.

Lastly, reliable, safe childcare in BC is costly and challenging to find. There are often long waitlists for out-of-home childcare in urban centres, which can disadvantage women disproportionately, creating even more obstacles to entering the workplace.

Further Reading

- “8 Basic Barriers to Indigenous Employment” (Joseph, 2019)

- “Insight on 10 Myths About Indigenous Peoples” (Joseph, 2018)

- Dispelling Common Myths about Indigenous Peoples (Joseph, 2021)

- Dispelling the Misconceptions About Indigenous People (Circles for Reconciliation, 2020)

- “Pulling Together: Foundations Guide — Appendix C: Myths and Fact?” (Wilson, 2014)

- “What Exactly Is a Microaggression?” (Desmond-Harris, 2015)

Rights & Responsibilities Frameworks

Truth & Reconciliation: Calls to Action

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) recommended a series of 94 Calls to Action (CTA) (Reconciliation Education, n.d.) that outlined various actions by several sectors to support, foster, and develop reconciliatory action that would transform institutions and systems for Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Everything from education, sports, employment, and more was tasked with action.

Specifically, CTA 92 called for the “corporate sector in Canada to adopt the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as a reconciliation framework, and to apply its principles, norms, and standards to corporate policy and core operational activities involving Indigenous peoples and their lands and resources” (TRC, 2015a). In fact, it was not until 2019 that BC adopted UNDRIP.

In terms of employment and career planning, CTA 92ii and 92iii are particularly important to explore. The TRC uses wording that welcomes expansive action on the part of employers and individuals. CTA 92ii mandates that employers ensure that Indigenous Peoples have “equitable access to jobs, training, and education opportunities in the corporate sector” (TRC, 2015a). The second aspect of CTA 92ii calls for communities to gain long-term sustainable benefits from economic development projects, which also has an impact on potential employment for Indigenous community members.

TRC Call to Action 92: Business & Reconciliation

We call upon the corporate sector in Canada to adopt the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as a reconciliation framework and to apply its principles, norms, and standards to corporate policy and core operational activities involving Indigenous peoples and their lands and resources. This would include, but not be limited to, the following:

- 92i: Commit to meaningful consultation, building respectful relationships, and obtaining the free, prior, and informed consent of Indigenous peoples before proceeding with economic development projects.

- 92ii: Ensure that Aboriginal peoples have equitable access to jobs, training, and education opportunities in the corporate sector and that Aboriginal communities gain long-term sustainable benefits from economic development projects.

- 92iii: Provide education for management and staff on the history of Aboriginal peoples, including the history and legacy of residential schools, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Treaties and Aboriginal rights, Indigenous law, and Aboriginal–Crown relations. This will require skills-based training in intercultural competency, conflict resolution, human rights, and anti-racism

(TRC, 2015a).

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

The second framework is the United Nations (2007) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), and it was only recently adopted in BC. UNDRIP was adopted by the UN General Assembly on September 13, 2007. It was only in 2019 that Canada officially supported UNDRIP, having voted against it in 2007. It is a framework that asserts that Indigenous peoples should be free from discrimination. The framework can be summarized as a mechanism to protect Indigenous peoples’ rights to cultural integrity, education, health, and political participation. UNDRIP also recognizes Indigenous Peoples’ rights to their lands and natural resources and the observation of their treaty rights.

This has significant implications for employment rights and, along with the TRC’s Calls to Action, has influenced organizations to create more Indigenous recruitment programs and focus on diversifying their organizations. UNDRIP Article 17 (Parts 1 and 3) and Article 21 refer to economic protections and employment. Explore Article 17, which asserts the rights of Indigenous Peoples in the area of labour law and establishes the right to not be discriminated against, below.

UNDRIP Article 17

- Article 17-1. Indigenous individuals and peoples have the right to enjoy fully all rights established under applicable international and domestic labour law.

- Article 17-3. Indigenous individuals have the right not to be subjected to any discriminatory conditions of labour and, inter alia, employment or salary.

(United Nations, 2007)

Parts 1 and 3 of Article 17 mean that the rights of Indigenous peoples are protected, and they should be able to enjoy a harassment-free environment at work. It also means that you cannot be refused employment or be discriminated against based on your cultural background. If you find that this is the case, steps to rectify the discrimination would be to consult your university co-op coordinator (if you are a co-op student) and/or your human resources advisor at your organization.

The Labour Program: Changes to the Canada Labour Code (ESDC, 2021) lists recent improvements to employee rights. It is a good resource to review, whether you are just entering the workforce or if you have already been a part of the workforce because it details your rights and entitlements. For example, did you know Indigenous employees are entitled to five days off for cultural practices?

This brings us to a discussion about UNDRIP Article 21, which details provisions for economic conditions and areas regarding employment and training, as well as particular attention to those who are historically marginalized: women, Elders, youth, children, and those with disabilities.

UNDRIP Article 21

- Indigenous peoples have the right, without discrimination, to the improvement of their economic and social conditions [emphasis added], including, inter alia, in the areas of education, employment, vocational training and retraining [emphasis added], housing, sanitation, health and social security.

- States shall take effective measures and, where appropriate, special measures to ensure continuing improvement of their economic and social conditions [emphasis added]. Particular attention shall be paid to the rights and special needs of Indigenous elders, women, youth, children and persons with disabilities.

(United Nations, 2007)

Article 21 speaks to the fact that the government has a commitment to supporting Indigenous individuals to improve their economic conditions, including employment, and it codifies taking special measures for continuous improvement. The result of this mandate is increasing opportunities for Indigenous Peoples in employment, in which organizations are answering the call to increase diversity. Yet despite adopting UNDRIP, it still has no legal authority in Canada.

The following timeline is not an exhaustive list of events, but it identifies key events in the Indigenous rights framework. See Appendix O: Indigenous Rights Based Framework Timeline — TRC, UNDRIP & Reports for a long description of this timeline.

If you are using a printed copy, you can scan the QR code with your digital device to go directly to Timeline: Canada’s Reconciliation and Rights — Some Key Milestones TRC, UNDRIP

What Does This Mean for Indigenous Canadians Seeking Employment?

As a result of the TRC, many organizations have increased their attention to developing recruitment strategies designed to employ Indigenous Canadians, with a goal to diversify their workplace in the hope of closing the gap that exists between non-Indigenous and Indigenous Canadians regarding employment statistics. This can result in increased opportunities for Indigenous employment candidates.

As Canadians become aware of the history and legacy of cultural oppression, genocide, and the resulting lack of access to education and employment opportunities for Indigenous Canadians, employers have been urged to take action to close this gap in employment between non-Indigenous and Indigenous Canadians. CTA 92ii is integral to educating employers and supporting leaders and management with intercultural training, human rights awareness, anti-racism, and implicit bias training that may improve hiring practices. This training is key to increasing Indigenous employment, improving diversity in the workplace, and creating safer employment spaces for Indigenous Canadians.

Exercise 15.2

Reflect on the Implications of TRC’s Calls to Action

Take a look at the TRC’s (2015a) Calls to Action report, and locate the specific CTA(s) for the sector in which you plan to work. Reflect on the following questions:

- What do the CTAs mean for you in the workplace, and what do they mean for the organization?

- Is there evidence of action on the organization’s website?

- Does the organization have evidence of professional development or educational opportunities for its employees?

- What are some reconciliatory actions you can do to support diversity in the workplace?

Further Reading

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action (2015a), full report

- Beyond 94: Truth and Reconciliation in Canada (Barrera. et al., 2021), CBC report on the progress toward TRC Calls to Action

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) (United Nations, 2007)

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples [PDF] (United Nations, 2007), the full document and overview

- United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues: Frequently Asked Questions on Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (United Nations, n.d.), a summary and FAQ

- International Human Rights Principles What Are Human Rights? (Amnesty International, n.d.), a summary of UNDRIP

- What Does “Implementing UNDRIP” Actually Mean? (Last, 2019), CBC News analysis

- Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (“Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,” 2021)

Racism & Implicit Bias

Indigenous students are not always in culturally-safe on campus. The concept of cultural safety recognizes that we need to be aware of and challenge unequal power relations at all levels: individual, family, community, and society (Cull et al., 2018). The reality is that many Indigenous students experience racial microaggressions daily, and this ongoing harm creates feelings of isolation and not being welcome. A racial microaggression is a “subtle behaviour that [conveys] hostile, derogatory, or negative messages to persons of marginalized groups” (Shotton, 2017, p. 33).

A Catalyst survey defines the concept of an “emotional tax” as an extra psychological burden at work (Thorpe-Moscon et al., 2019). This emotional tax, and the low levels of psychological safety that Indigenous Peoples experience, are not shared by mainstream or non-marginalized employees. In more detail, emotional tax is “the combination of feeling different from peers at work because of gender, race, and/or ethnicity, being on guard to experiences of bias” (Thorpe-Moscon et al., 2019) and it is linked to employee retention and health and well-being.

According to a recent article, Indigenous workers describe feeling “on guard” and that they have to follow a higher code of conduct than their non-Indigenous peers (Deschamps, 2021). They may take special care not to reinforce stereotypes about Indigenous peoples; for example, they may feel added pressure to always show up on time, never over-drink at work functions, and present as “agreeable” so as not to appear “angry” (Deschamps, 2021). These behaviours are ways that Indigenous employees protect themselves from bias and discrimination because they do not have the same privilege as their non-Indigenous peers. Feeling on guard or unsafe has ramifications for diversity in the workplace.

Because a large proportion (60%) of Indigenous workers feel unsafe on the job, their overall sense of belonging is impacted (Deschamps, 2021). This influences the way these workers navigate employment and career choices. It may influence how many Indigenous individuals seek work in their home communities where they have connections, support, and resources.

The Indigenous artist Jarrid Poitras outlines ways in which comments made in the workplace impact Indigenous Peoples and how complicated it is to advocate for yourself. You can read more about Jarrid Poitras’s story in the CBC News article “‘Pawn it’ Comment Prompts Indigenous Artist to Call out Discrimination in Sask. Country Music Industry” (Latimer, 2021).

Unfortunately, Indigenous women are impacted by this “on guard” feeling disproportionately—67% of Indigenous women, as opposed to 38% of men—and this lack of comfort leads to reduced progression, inability to voice their opinions, and ignoring microaggressions or colleague’s unconscious biases out of fear of not being amenable to corporate culture (Deschamps, 2021). The high percentage of Indigenous workers who feel unsafe in the workplace has implications for company leadership. Leaders must provide a safe and welcoming space for Indigenous employees to be themselves. Indigenous workers should not feel penalized for raising concerns or challenges. They should feel their Indigeneity is accepted, rather than having to educate colleagues or the company. Determining whether an employer has a solid reconciliation or decolonization initiative is a good sign that there is progress in that particular workplace.

Finding Support

Many organizations are realizing the need for Indigenous support, and they are adapting their practices to include cultural awareness or sensitivity training for employees at all levels (Deloitte, 2012). Take advantage of these workshops and professional development, so you can develop cultural sensitivity and improve your allyship with Indigenous colleagues. While organizations are improving their practices and policies, looking for support and mentorship is important. For example, Krystal Abotossaway, TD Bank Group’s Senior Manager of Diversity and Inclusion, indicates that “being able to draw on the organization’s network and connect with people who have faced challenges like hers has helped her professionally, where she finds the need to be ‘on guard’ has been melting away” (Deschamps, 2021).

Indigenous employees in mainstream workplaces often feel burdened, and they experience challenges that adversely influence their cultural safety and well-being. The concept of “working in two worlds” might be new to many cross-sector agencies, but for Indigenous employees, it can be a barrier to career satisfaction and progression. Often, Indigenous peoples are asked to educate their colleagues or be the go-to person for bringing cultural awareness to a team or department.

Suggestions are for organizations to maintain their own resources and ensure they are providing professional development for staff, so the onus for this development is not on Indigenous employees. Deloitte (2012) reported that Indigenous employees remarked on how “exhausting” it is to constantly be providing this cultural education. If you find that is occurring in your workplace, you can always suggest that your colleagues or workplace engage in external training. Some of those courses and resources can be found in Appendix N: Resources To Increase Your Knowledge About Indigenous Peoples.

Cultural sensitivity education and knowledge about the history of Indigenous peoples in Canada can support non-Indigenous employees to be better allies to our Indigenous colleagues without putting the burden of education on them. Additionally, non-Indigenous employees can support Indigenous colleagues by advocating and supporting a colleague if they find themselves witnessing an instance of cultural bias, derogatory comment, or racism in the workplace. As a victim or target of racism or cultural bias, it is difficult to advocate for oneself. If a non-Indigenous colleague notices this behaviour and calls it out, it can be more effective and create an increasingly safe environment for those impacted by these incidents. If you have more privilege or psychological safety than others, it is important that you use your voice as an ally.

The lack of psychological safety inhibits the career progress made by Indigenous employees, and it can limit the potential of the organization (Deschamps, 2021). High psychological safety is associated with many positive outcomes, both for Indigenous employees and their companies. Previous research indicates that the “emotional tax” may be diminished when leaders create an empowering work environment so that BIPOC employees have the autonomy, resources, and support they need to succeed (Thorpe-Mascon et al., 2019).

Allyship Strategies For Your Workplace

- Build relationships with Indigenous colleagues.

- Call out racist or biased comments.

- Demonstrate inclusivity.

- Create more space for Indigenous voices by encouraging everyone to be heard, especially in meetings.

- Champion your colleagues’ ideas and creativity.

- Educate yourself on the history of racism and oppression in Canada. Do not ask your colleague to educate the department or organization, unless that is their role in the company.

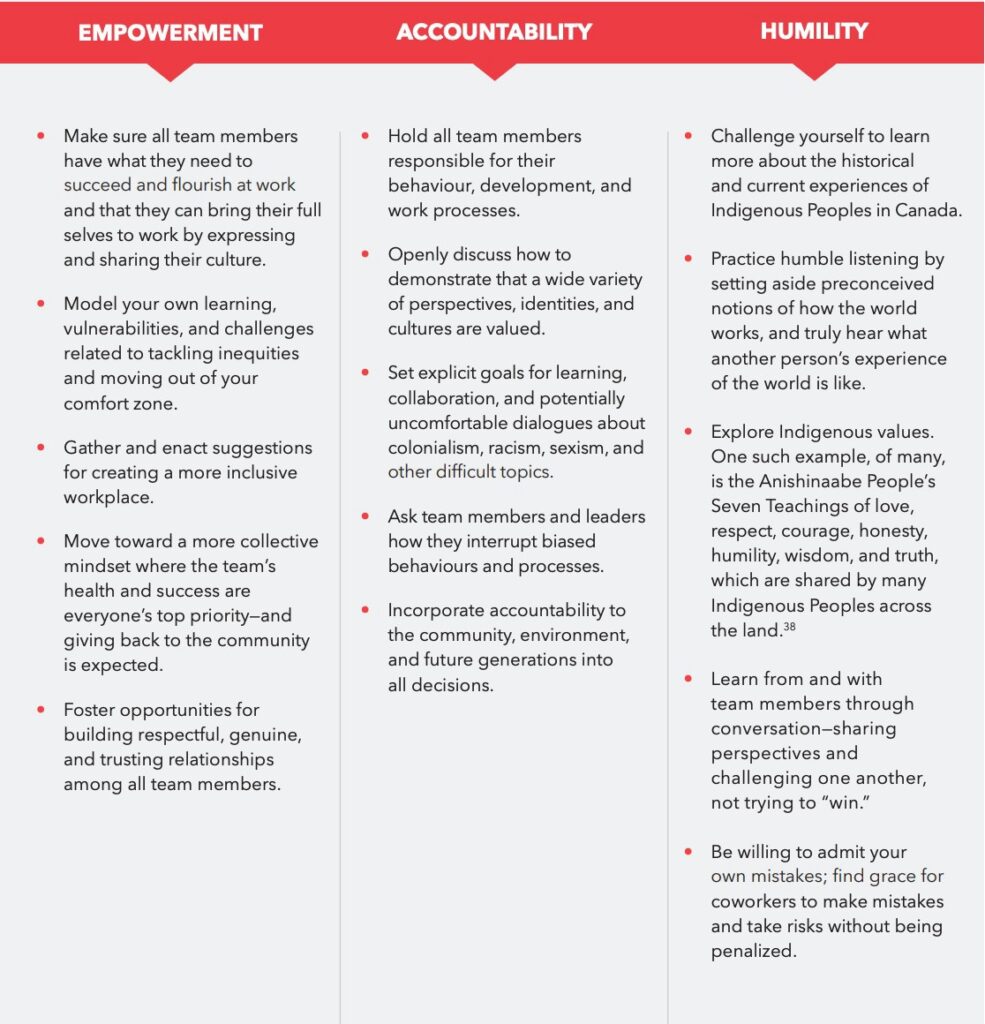

By modeling these behaviours, you will be signaling to other colleagues how to conduct themselves in an ethical fashion that supports reconciliation. The Application Process section in the Indigenous Inclusion in Employment chapter discusses how to determine the fit of a potential workplace by carefully assessing the organization’s EDI plan. This is a good first step and may reduce the challenges you face with regard to racism, bias, and inclusion if there is evidence that the organization has begun to do some of this work. Figure 15.2 includes various actions that can support reconciliation efforts, either as a non-Indigenous ally or as an Indigenous person (Thorpe-Moscon et al., 2019). Most of the actions are directed at managers and those who supervise employees. However, this infographic is helpful for outlining various collegial strategies that can be used across many positions in the organization, all the way from leadership positions to peers.

Exercise 15.3

Reflection: How Can You Support Indigenous Colleagues

Describe some of the ways that you can support an Indigenous colleague or advocate for yourself.

- List some actions that you can perform.

- What are some resources available to you?

- What aspects of a workplace would encourage you to feel safe coming forward?

- Give some thought about why you may not feel safe doing so. Link this with a recent or current experience.

Further Reading

- “‘Pawn it’ Comment Prompts Indigenous Artist to Call Out discrimination in Sask. Country Music Industry” (Latimer, 2021)

- “60% of Indigenous Workers Feel Emotionally Unsafe on the Job: Catalyst Survey” (Deschamps, 2021)

- Building Inclusion for Indigenous Peoples in Canadian Workplaces (Thorpe-Moscon & Ohm, 2020)

- Empowering workplaces combat emotional tax for people of colour in Canada (Thorpe-Moscon et al., 2019)

Media Attributions

- Figure 15.1 “Chart 1: Proportion of the population aged 15 to 24 years by Indigenous identity, Canada, 2016” [data from Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 2016] by Thomas Anderson (2021) is used under the Statistics Canada Open License.

- Figure 15.2 “Strategies to support Indigenous colleagues in the workplace” [using information from Thorpe-Moscon & Ohm (2021)] by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

Amnesty International. (n.d.). Indigenous Peoples’ rights. Retrieved February 24, 2025, from https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/indigenous-peoples/

Anderson, T. (2021). Chapter 4: Indigenous youth in Canada (Catalogue No. 42-28-0001). Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/42-28-0001/2021001/article/00004-eng.htm

Arriagada, P., & Hango, D. (2016). Literacy and numeracy among off-reserve First Nations people and Métis: Do higher skill levels improve labour market outcomes? (Catalogue No. 75-006-X). Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2016001/article/14630-eng.htm

Barrera, J., Beaudette, T., Bellrichard, C., Brockman, A., Deuling, M., Malone, K., Meloney, N., Morin, B., Monkman, L., Oudshoorn, K., Warick, J., & Yard, B. (2018, March 19). Beyond 94: Truth and reconciliation in Canada. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/newsinteractives/beyond-94/

BC Treaty Commission. (n.d.). Interactive map [Map]. http://www.bctreaty.ca/map

Canadian Human Rights Commission. (2020). Significant employment barriers remain for Indigenous people in banking and financial sector. http://web.archive.org/web/20241110093226/https://www.chrc-ccdp.gc.ca/en/resources/significant-employment-barriers-remain-indigenous-people-banking-and-financial-sector

Circles for Reconciliation Gathering Theme. (2022). Dispelling the misconceptions about Indigenous people (Manitoba version) [PDF]. https://circlesforreconciliation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/8-202203-Dispelling-the-Misconceptions-about-Indigenous-People-MB-Version.pdf

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, s 35, Part 1 of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/const/FullText.html

Cull, I., Hancock, R. L. A., McKeown, S., Pidgeon, M., & Vedan, A. (2018, September 5). Pulling together: A guide for front-line staff, student services, and advisors. BCcampus. https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationfrontlineworkers/

Declaration on the rights of Indigenous Peoples. (2021, March 16). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Declaration_on_the_Rights_of_Indigenous_Peoples&oldid=1012513741

Deloitte. (2012). Widening the circle: Increasing opportunities for Aboriginal people in the workplace. https://www2.deloitte.com/ca/en/pages/about-deloitte/articles/widening-the-circle-for-aborginal-people.html

Deschamps, T. (2021, February 10). 60% of Indigenous workers feel emotionally unsafe on the job: Catalyst survey. Toronto Star. https://www.thestar.com/business/2021/02/10/60-of-indigenous-workers-feel-emotionally-unsafe-on-the-job-catalyst-survey.html

Desmond-Harris, J. (2015, February 16). What exactly is a microaggression? Vox. https://www.vox.com/2015/2/16/8031073/what-are-microaggressions

Employment and Social Development Canada. (2023). About the Indigenous skills and employment training program. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/indigenous-skills-employment-training.html

Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC). (2021). Labour program: Changes to the Canada Labour Code and other acts to better protect workplaces. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/laws-regulations/labour/current-future-legislative.html

First Nations & Indigenous Studies. (2009). Welcome to Indigenous foundations. University of British Columbia. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/

First Peoples Cultural Council. (n.d.). First Peoples’ map of BC [Map]. https://maps.fpcc.ca/

Indian Act, RSC 1985, c I-5. https://canlii.ca/t/5439p

Joseph, B. (2018, November 27). Insight on 10 myths about Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/insight-on-10-myths-about-indigenous-peoples

Joseph, B. (2019, December 8). 8 basic barriers to Indigenous employment. Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/8-basic-barriers-to-indigenous-employment

Joseph, B. (2021). Dispelling common myths about Indigenous Peoples: 9 myths and realities. Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. https://www.ictinc.ca/dispelling-common-myths-about-indigenous-peoples

Julien, M., Somerville, K., & Brant, J. (2017). Indigenous perspectives on work-life enrichment and conflict in Canada. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, 36(2), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-11-2015-0096

Last, J. (2019, November 2). What does implementing UNDRIP actually mean? CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/implementing-undrip-bc-nwt-1.5344825

Latimer, K. (2021, February). ‘Pawn it’ comment prompts Indigenous artist to call out discrimination in Sask. country music industry. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/sask-country-music-association-remarks-1.5916861?fbclid=IwAR3mbd_frgkWjJMdVhSPabiHWTsHlcqQoXAsUOnapVC8ff-bqgbUg2TgQEk

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Microaggression. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved February 26, 2025, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/microaggression

Native Land Digital. (n.d.). Native land [Map]. https://native-land.ca/

Ojibwe.net. (n.d.). The gifts of the seven grandfathers. https://ojibwe.net/projects/the-gifts-of-the-seven-grandfathers/

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2018). Indigenous labour market outcomes in Canada. In Indigenous employment and skills strategies in Canada. OECD Reviews on Local Job Creation. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264300477-en

Overmars, D. (2019). Wellbeing in the workplace among Indigenous People: An enhanced critical incident study [Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia]. UBC Theses and Dissertations. https://doi.org/10.14288/1.0378430

Rao, K., & Tilt, C. (2015). Board composition and corporate social responsibility: The role of diversity, gender, strategy and decision making. Journal of Business Ethics, 138, 327–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2613-5

Reconciliation Education. (n.d.). What are the 94 Calls to Action? https://www.reconciliationeducation.ca/what-are-truth-and-reconciliation-commission-94-calls-to-action

Shotton, H. J. (2017). “I thought you’d call her White Feather”: Native women and racial microaggressions in doctoral education. Journal of American Indian Education, 56(1), 32–54. https://doi.org/10.5749/jamerindieduc.56.1.0032

Southern First Nations Network of Care. (n.d.). The seven teachings. https://www.southernnetwork.org/site/seven-teachings

Statistics Canada. (2025). Archived – Labour force characteristics by region and detailed Indigenous group, inactive (Table no. 14-10-0365-01) [Table]. https://doi.org/10.25318/1410036501-eng

Statistics Canada. (2012). Aboriginal peoples: Fact sheet for Canada (Catalogue no. 89-656-X). https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-656-x/89-656-x2015001-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2017a). Aboriginal peoples highlight tables, 2016 Census (Catalogue no. 98-402-X2016009). https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/hlt-fst/abo-aut/index-eng.cfm

Statistics Canada. (2017b). Aboriginal peoples in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census (Catalogue no. 11-001-X). The Daily. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025a-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2018a). First Nations people, Métis and Inuit in Canada: Diverse and growing populations (Catalogue no. 89-659-X). https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-659-x/89-659-x2018001-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2018b). National Indigenous Peoples Day…by the numbers. http://web.archive.org/web/20240918185430/https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/dai/smr08/2018/smr08_225_2018

Statistics Canada. (2020, January). 2016 census Aboriginal community portrait – Canada (Catalogue no. 41260001) [Image]. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/abpopprof/infogrph/infgrph.cfm?LANG=E&DGUID=2016A000011124&PR=01

Thorpe-Moscon, J., & Ohm, J. (2021). Building inclusion for Indigenous Peoples in Canadian workplaces. Catalyst. https://ccwestt-ccfsimt.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/IndigenousPeoplesCanadaReport_English_final.pdf

Thorpe-Moscon, J., Pollack, A., & Olu-Lafe, O. (2019). Empowering workplaces combat emotional tax for people of colour in Canada. Catalyst. https://www.catalyst.org/insights/2019/emotional-tax-canada

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015a). Calls to action [PDF]. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/british-columbians-our-governments/indigenous-people/aboriginal-peoples-documents/calls_to_action_english2.pdf

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015b). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (Catalogue no. IR4-7/2015E-PDF). Government of Canada. http://publications.gc.ca/pub?id=9.800288&sl=0

United Nations. (n.d.). Indigenous Peoples Indigenous voices: Frequently asked questions — Declaration on the rights of Indigenous Peoples [PDF]. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/faq_drips_en.pdf

United Nations. (2007, September 13). United Nations declaration on the rights of Indigenous Peoples [UNGAOR, 61st Sess, UN Doc A/RES/61/295]. https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html

University of Alberta. (n.d.). Indigenous Canada [Online course]. https://www.ualberta.ca/admissions-programs/online-courses/indigenous-canada/index.html

University of British Columbia. (n.d.). Reconciliation through Indigenous education [Online course]. https://pdce.educ.ubc.ca/reconciliation/

Long Descriptions

| Indigenous Identity | Percent |

|---|---|

| Total Indigenous Population | 16.9 |

| First Nations People | 17.5 |

| Métis | 16 |

| Inuit | 18.4 |

| Non-Indigenous Population | 12 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 2016

Figure 15.2 Long Description: Thorpe-Moscon & Ohm (2021) identify strategies for supporting Indigenous colleagues in the workplace (p. 8). The supporting strategies, divided into three categories—empowerment, accountibility and humility—are as follows:

Empowerment:

- Make sure all team members have what they need to succeed and flourish at work and that they can bring their full selves to work by expressing and sharing their culture.

- Model your own learning, vulnerabilities, and challenges related to tackling inequities and moving outside your comfort zone.

- Gather and enact suggestions for creating a more inclusive workplace.

- Move toward a more collective mindset where the team’s health and success are everyone’s top priority—and giving back to the community is expected.

- Foster opportunities for building respectful, genuine, and trusting relationships among all team members.

Accountability:

- Hold all team members responsible for their behaviour, development, and work processes.

- Openly discuss how to demonstrate that a wide variety of perspectives, identities, and cultures are valued.

- Set explicit goals for learning, collaboration, and potentially uncomfortable dialogues about colonialism, racism, sexism, and other difficult topics.

- Ask team members and leaders how they interrupt biased behaviours and processes.

- Incorporate accountability to the community, environment, and future generations into all decisions.

Humility:

- Challenge yourself to learn more about the historical and current experiences of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

- Practice humble listening by setting aside preconceived notions of how the world works, and truly hear what another person’s experience of the world is like.

- Explore Indigenous values. One such example, of many, is the Anishinaabe People’s Seven Teachings of Love, respect, courage, honesty, humility, wisdom, and truth, which are shared by many Indigenous Peoples across the land.*

- Learn from and with team members through conversation-sharing perspectives and challenging one another, not trying to “win.”

- Be willing to admite your own mistakes; find grace for coworkers to make mistakes and take risks without being penalized.

*The Seven Teachings (Southern First Nations Network of Care, n.d.); The Gifts of the Seven Grandfathers (Ojibwe.net, n.d.).