2. Self-Assessment

Harshita Dhiman and Noah Arney

[This chapter is adapted from a previous version by Mitch Clingo]

Introduction

Assessment has been a core element of career development since the beginning of the 20th century. Career theory began early on with the belief that if you had an accurate understanding of an individual’s traits, the person could then be matched to their ideal profession. While we understand that career-pathing is more intricate than this matching process, a strong self-understanding still creates a solid foundation for vocational exploration, self-promotion, and informed career decision-making (Metz & Jones, 2013). Today, the focus of most career assessments is on the meaning-making that an individual does with the results of the assessment. In many cases, externally administered assessments have been replaced with self-assessments. Engaging with career assessments can help immensely in moving from a state of unawareness to opportunity.

This chapter explores the most common dimensions of self-awareness—personality, interests, and abilities—that have traditionally been measured through quantitative assessments (those that provide a categorical output). It will also look at modern qualitative assessments that seek to create self-awareness through a dialogue of self-reflection and meaning-making.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Recognize three dimensions of personal awareness: skills, values, and personality.

- Critically consider the differences and strengths of qualitative and quantitative assessments.

- Apply a qualitative self-assessment to explore your skills.

Personal Awareness

Personality

When deciding on a career path, it is important to consider whether your personality aligns well with the job requirements. Personality is a staple of self-awareness. It is the individual set of behaviours, cognitions, and emotional patterns that arise from biological and environmental factors (Burch & Anderson, 2009). Aligning a job role with an individual’s personality traits tends to exhibit higher levels of productivity (Riggio, 2018).

Not every personality is suitable for every job, so it is important to understand your own personality traits to make more appropriate and realistic occupation choices. For example, extroverted people are more productive in a work environment where they interact with others; whereas, introverted people often work well in a work environment with no or less social interaction.

Interests

Considering interests during career planning can provide valuable insight into potential career paths. Interest can be described as a condition in which an individual is actively involved or has a natural inclination or desire to engage in an activity (Hidi & Renninger, 2006). Interest awareness can help an individual identify what motivates them in life. In the process of self-assessment, finding career indicators within one’s interest creates a promising path to achieve career success. Tools like career interest inventories, such as RAISEC, can help individual explore their interests and relate them to different career options.

Interestingly, while it is important to consider these factors when choosing a career, these factors are not set in stone. Research has shown that personality traits and RAISEC interests are impacted by the careers we choose. Regardless of what you choose, your personality and interests will moderately change to match your chosen field (Wille & De Fruyt, 2014). The things we enjoy doing outside of work and the things we are happy to do as part of our work context are often very different.

Values

Values are the beliefs and principles that influence an individual’s behaviour and decisions. Values act as benchmarks or guidelines that offer social validation for decisions and actions (Rokeach, 1973). Understanding and focusing on our individual values can assist you in identifying job prospects that closely match your core beliefs, thereby fostering greater confidence during interviews. For instance, if you prioritize stability, you may seek roles characterized by consistent tasks, fixed daily schedules, and a steady work environment. Value recognition can not only help you select a career but also help you make more informed decisions in the workplace.

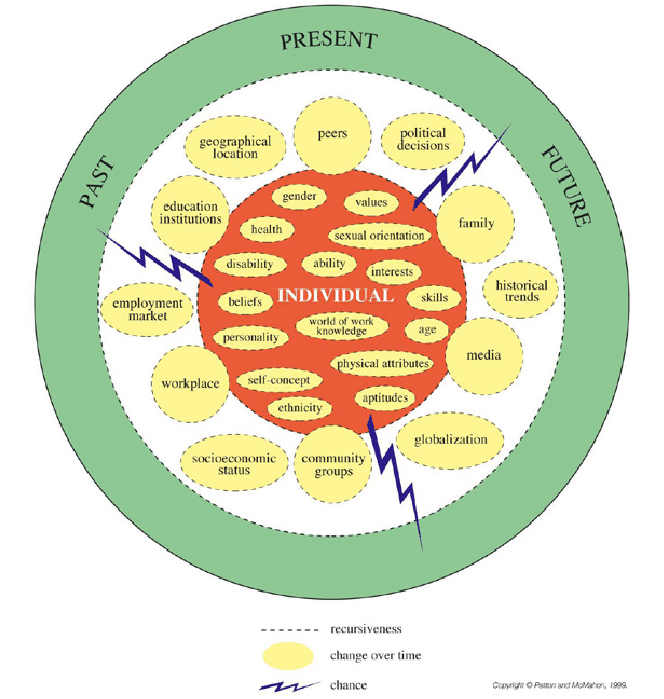

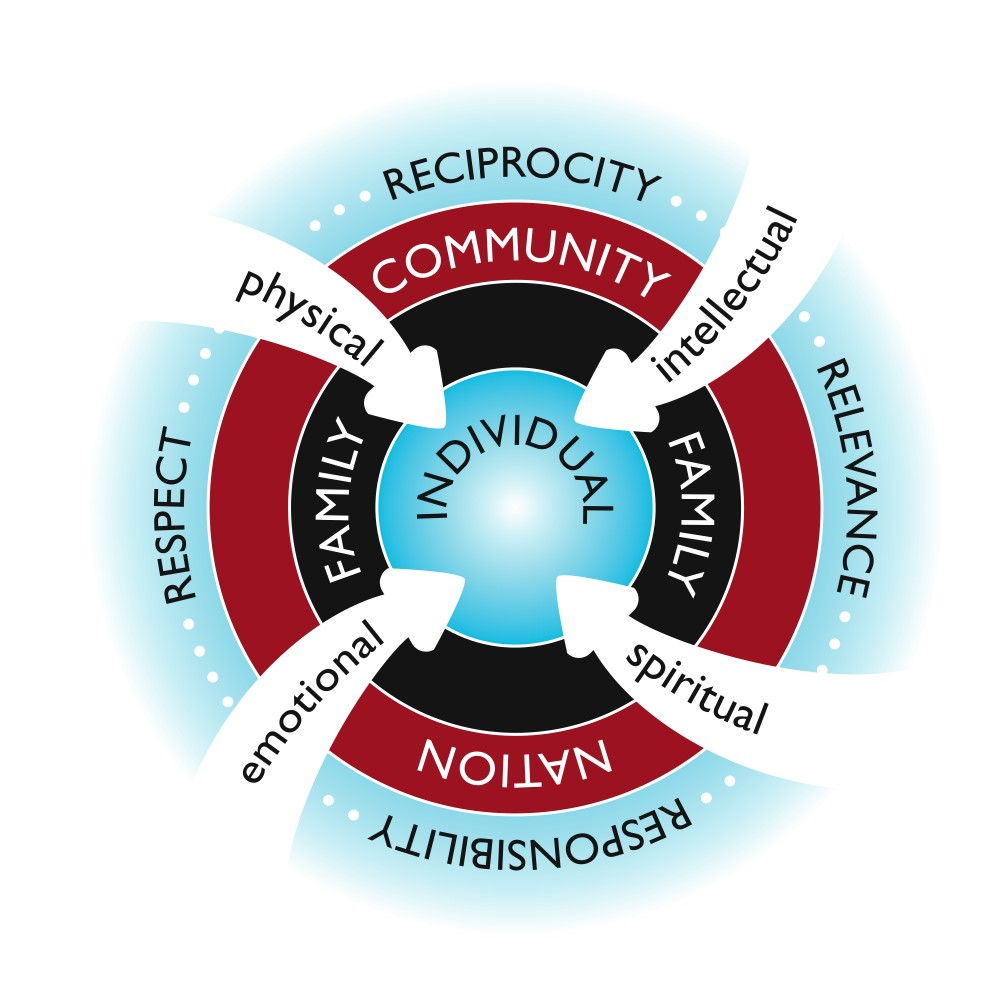

Holistic Self

One way of understanding values is to consider yourself within a complex set of contexts and relationships. These contexts and relationships all impact how we interpret our values and how we perceive our self. There are a number of ways to visualize these interconnected contexts, but two for you to consider today are the systems theory framework for career development (STF) (Figure 2.1), created by Wendy Patton and Mary McMahon (1999), and the Indigenous wholistic framework (IWF) (Figure 2.2), created by Michelle Pidgeon (2014).

Indigenous Ways of Knowing and Being] CC BY 4.0 [Long Description]

When using these frameworks to understand your holistic self, consider how you interact with each part of your self and in what context you connect with others or aspects of yourself and aspects of others. How do you connect with family or community regarding your goals, hopes, or values? How does what another person does (i.e., the choices they make) impact your values or perception of yourself?

Skills & Abilities

Over the past two decades, the discussion of career preparedness in Canada has shifted its focus to skills (Viczko et al., 2019) and abilities. This shift means that instead of looking at markers expected to mean that a person has certain skills and abilities (like a university degree in certain disciplines), employers are more likely to want to know what specific skills a candidate has. For a very long-time, skills discussion focused mostly on skills that are specifically applicable to individual jobs (i.e., technical skills), with broader skills that are interpersonal, social, and emotional in nature being described as “soft skills.” Today, these skills are considered more important than ever and, in some industries, are considered more important than technical skills. To show this equality, the terms “technical skills” and “transferable skills” (Arney & Krygsman, 2022) will be used here.

Skill and ability assessments have traditionally been used to determine an individual’s potential for specific types of work (Metz & Jones, 2013). However, because in the 21st century, we emphasize choosing a career rather than being matched to it, skills assessments are now seen as part of career exploration and planning. You identify skills you enjoy doing well and then consider roles in which you will get to do those skills frequently.

Skills or ability assessments evaluate strengths and weaknesses in relation to work. Once a career path has been chosen, this awareness is used to set goals for coursework and experiential opportunities to amend skill deficits or enhance strengths (Metz & Jones, 2013). Skills assessments can be further used to better articulate self-promotion and career pathing.

Technical Skills

Technical skills are the skills you use in a job, profession, career, or role that are specific to that area and less impactful in other fields, such as the types of tools or techniques used. What it does not include are broadly applicable skills, such as communication or teamwork skills.

Many of these skills are taught in discipline-specific classes within a post-secondary program. Take a moment to consider the tools, techniques, and methods taught in your program or discipline-specific classes. If you are struggling to identify them, find a few jobs, preferably entry level, that are specific to your discipline and identify common things they ask for that do not show up on job postings outside of your industry or field.

Technical Skill Examples

- Electrician: A specific way to wiring an outlet according to code.

- Accountant: The ability to use the software Sage 50.

- Health Care Assistant: A specific way of moving a patient.

- Scholar of English: The methodology of literary criticism.

Transferable Skills

Although there are a lot of frameworks for transferable skills (Arney, 2021), the most common skills listed in them are critical thinking, collaboration, communication, and creativity. Sometimes life-long learning and self-management are included as well. The use of a transferable skills framework is helpful for being able to specify what you mean when you talk about your skills. For example, many students find it difficult to explain why they have good communication skills or how they can display or describe collaboration. In Canada, the new Skills for Success framework (expanded and reworked from the Essential Skills framework) is a strong choice for understanding your skills and how you can explain them to an employer in a way they will understand (Employment and Social Development Canada [ESDC], 2024a).

Skills for Success

Reading, writing, numeracy, and digital skills remain the foundation of the Skills for Success framework, but the transferable skills of problem solving, creativity and innovation, communication, collaboration, and adaptability are given new prominence (Figure 2.3) (ESDC, 2024a). Each of the nine skills has six components, which give aspects of the skill that you can consider. For example, one of the components of creativity and innovation is “facilitate a creative and innovative environment.” (ESDC, 2024b). These components allow you to think critically about your skill level in a way that is more applicable than simply considering the broad skill.

The skills for success framework forms the basis of the assessment you will be trying out at the end of this chapter.

Quantitative Assessment

Quantitative assessments utilize standardized tests that are designed to measure individual’s specific skills. Examples of such assessments include psychometric tests, personality evaluations, and aptitude tests. These assessments primarily aim to determine one’s capability to perform certain tasks rather than their inclination towards them. Qualitative assessment results include a list of professions that will be most suitable to you in terms of job satisfaction and your chances of succeeding at it. For instance, an aptitude test for an entry-level computer programming position would assess whether the individual possesses the capacity to acquire the requisite skills for the field.

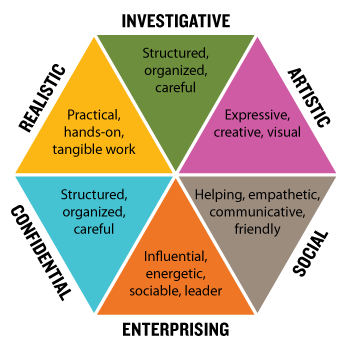

Holland

The best known model of vocational interests is the hexagonal model proposed by John Holland (Holland, 1997). Holland defines six categories (or types) based on sets of interests. These are known as either Holland codes or RIASEC types. In this model, as shown in Figure 2.4, interest types are organized onto the hexagram to imply stronger relations to closer types. For example, realistic is seated next to investigative because a person who scores higher on the realistic category is likely to score higher in investigative as well.

Holland (1997) believed workers would be happier in the environment they were most interested in. There are several self-assessments available online that measure your interest in the six categories and provide your top three dominant types as a measure of occupational suitability. However, there are criticisms for using interests to steer career explorers to specific career areas (Spokane et al., 2002). Evidence does not support high job satisfaction simply based on interest alone. Furthermore, interest-based inventories do not account for the wide degree of “jobs” in any career area. For example, in the forestry industry, jobs range from machine operator to project manager. The responsibilities and skills required for those two roles are vastly different, even though they fall within the same career area of forestry.

Interest inventories are a great place to start with career exploration. They can provide insight into available jobs or careers based on self-reported personal information. Once careers are identified, career explorers can delve further into their area of interest through reality-based investigation, such as job shadowing, volunteering, course work, etc. This information should be used in conjunction with other strategies to make realistic and informed career decisions.

Exercise 2.1

RAISEC Assessment

Complete the Holland code (RIASEC) test from the Open-Source Psychometrics Project (2019): Holland Code (RIASEC) Test

After you complete the assessment, consider the following:

- Would your family and friends agree with your results?

- Were you surprised by any of the results?

- How have your interests guided your decision-making until now?

- Which suggestions from the assessment resonate with you most?

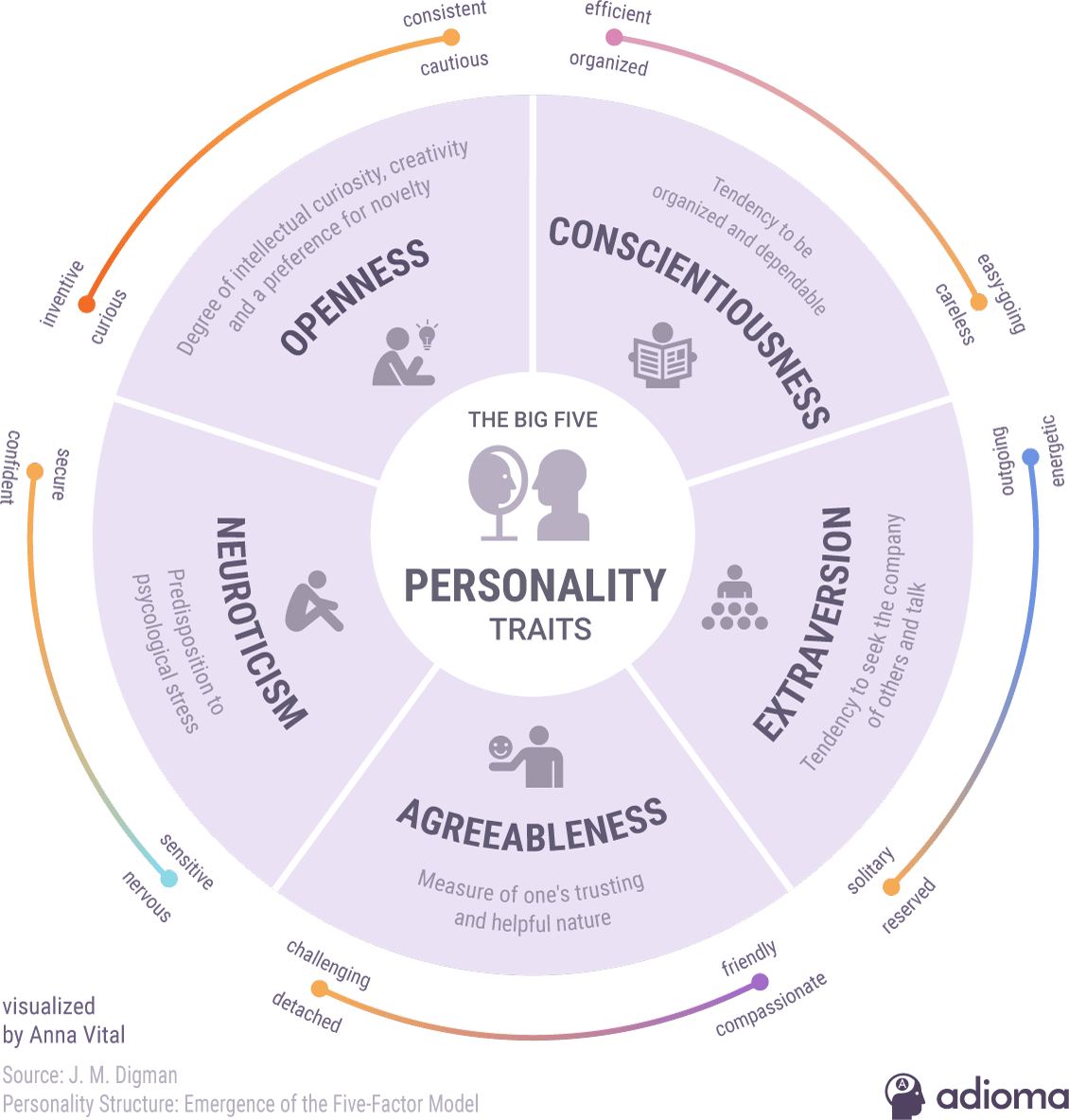

Five-Factor Model

Currently, the most dominant paradigm of personality is the five-factor model (as shown in Figure 2.5), also known as the “Big Five.” Each factor is a spectrum, with individuals able to score anywhere on the line. Each factor is also made up of multiple sub-factors.

The five factors of the model are:

- Openness to experience

- Conscientiousness

- Extroversion

- Agreeableness

- Neuroticism

Each personality trait has its own meaning. Understanding these traits help provide insight into your own personality. A different way of looking at the big five can be that “Extraversion is sociability, agreeableness is kindness, openness is creativity and intrigue, conscientiousness is thoughtfulness, and neuroticism often involves sadness or emotional instability” (Cherry, 2022). An easy way to remember the Big Five is through the acronym OCEAN or CANOE. There have been many theories and attempts to figure out how many personality traits exist, ranging from as little as three to 4,000 or more. With the Big Five, we are able to describe these broad traits in a building block style that creates our personality.

Personality has often been strongly considered in vocational choice because it represents characteristics that are largely stable over time (Spokane et al., 2002). Therefore, many researchers believe a successful career decision can be made by matching personality with corresponding occupations. For example, an individual who scores high in extroversion, characterized by sociability and talkativeness, is often recommended entrepreneurial careers such as sales and marketing.

However, research has struggled again to find clear correlations in this area (Guruge, 2021). It is difficult to find a consensus on what personality characteristics are most suited for a specific job. If a panel of experts were asked to determine the most valuable traits for a given occupation, different experts would suggest different traits. Using extroversion again as an example, you could assume it would be a valuable trait for counsellors or case managers. However, you could make another argument that introverts, who have a strong ability to connect with others in one-to-one scenarios, would be a better fit for these positions. Most occupations are made up of individuals with a wide range of personalities. Personality assessments are well-suited to initiate the process of self-reflection.

Being intentional about the skills you are developing and reflecting upon your experience once you are done leads to more effective career planning. See Figure 5.1 in Volunteering, which is based on Kolb’s experiential learning cycle and Lewin’s experiential learning model.

Exercise 2.2

Big 5 Personality Assessment

Complete the Big Five personality test from Truity (n.d.): Big Five Personality Test

After completing the assessment, consider the following:

- Would your family and friends agree with your results?

- Which result of the assessment do you most agree with?

- Which result of the assessment do you most disagree with?

- Which aspects of your personality do you feel impact your decision-making?

- How has your personality guided your decision-making until now?

Qualitative Assessment

Qualitative assessment is described as “informal forms of assessment” (Okocha, 1998, p. 151). “Qualitative career assessment stimulates storytelling, and in doing so, facilitates learning about oneself through self-reflection and enhanced self-awareness” (McMahon & Watson, 2019, para. 4). “Abilities predict occupational performance and success; interests and values predict occupational satisfaction” (Metz & Jones, 2013, p. 471).

Qualitative assessments are then used to understand the larger picture. These assessments emphasize your individual experiences, which affect the choices you make. They are more informal, flexible, open-ended, and holistic than quantitative assessments. They recognize the importance of stories and the intangible aspects that lead to career adaptability and satisfaction. Qualitative assessments also do a better job of taking into account the challenges and barriers that traditional assessments overlook (McMahon et al., 2019). Collaboration and cooperation with a career practitioner is encouraged to facilitate reflection, debriefing, and meaning-making.

Examples of qualitative assessments include My System of Career Influences (McMahon et al., 2017a; McMahon et al., 2017b; McMahon et al., 2013), which guides users through a structured process in a booklet format, and the Motivated Skills Card Sort (Knowdell, 2005), which provides a set of step-by-step instructions for users.

Career Construction

About one-third of qualitative career assessments fall under the broad career construction grouping (McMahon et al., 2019). This specific theory comes from Mark Savickas and explains how we apply meaning to our career paths, which are often much more complex today than when career theory first arose. What is important is not so much what the career paths have been but how we perceive and understand them. People do not make decisions randomly; they do what they feel is the best option or aligns with the themes or focuses of the person’s path so far. Career construction assessments, such as the career construction interview, focus on this.

Narrative Assessment

Many of the more recent career assessments are based off of a narrative understanding of career development (McIlveen & Patton, 2007; McMahon et al., 2019), making them the second most common qualitative tool currently used. What is meant by narrative is that what matters about career assessment is not what some outside test says but how it connects to the stories we tell ourselves about who we are and what we do. If an assessment says that you are a practical person, how does that fit into how you see yourself?

One of the common methods for this is based on Reinekke Lengelle and Frans Meijers’s (2015) work on “career writing,” where individuals and groups write reflectively on their current or potential career, their identity, and how they see themselves connecting with it. This helps people identify things they believe about themselves that are no longer true or relate to something that has changed too much for it to be useful anymore. It also helps build a narrative about what an imagined future could be like and how to achieve it.

My Career Story (Savickas & Hartung, 2012) is a way of blending the career writing and career construction methods. In this method, you write several very short stories about yourself based on prompts that touch on the things you admire or enjoy in media as well as career topics. The work is then blended together with questions and discussions before being rewritten into a story that talks about where you want to go next and advice to yourself about it.

The most important part here is how you create your own narrative and how you think about yourself and your options, limitations, and opportunities. By being explicit about these, you can often find places to improve or find limitations you have put on yourself that may no longer make sense. The process by which we make meaning in our own narrative is both how we limit ourselves and how we identify self-imposed limitations that can be overcome.

Subjective Reports Transferable Skills Assessment

One of the connection points between qualitative and quantitative assessments is that it needs to be something that provides a place for the person taking it to examine something about themselves. For qualitative assessments, this is meant as a starting point for reflection. To bring together your self-assessment in this chapter, you will use an assessment of your transferable skills to help you better understand what is meant by them and how you may already be using these skills in your professional and educational life.

The Subjective Reports Transferable Skills Assessment (Arney, 2024) is a tool to help walk you through the sub-skills or components of five of the Skills for Success skills. It provides additional information about what is meant by the component and how you may be able to demonstrate it. The subjective part is that this is done not based on practicing the skill and being reviewed quantitatively but is based on a qualitative and holistic perception of the skills in practice by the one using it.

Exercise 2.3

Subjective Reports Transferable Skills Assessment

Completing the Assessment

Each of the five skills has six components and each of those components has three different levels: building, enhancing, and proficient. A statement about an action you can do is given for each level of the component. Each level builds on the ones before.

In scoring the assessment, reflect on times when you have done the actions within each component and level. Write down, circle, or mark the highest-level actions you are frequently able to do for each component of each skill.

Reflection: How many times did you circle building, enhancing, or proficient for each of the skills? What skills did you score yourself higher on than you expected? How often do you think you can demonstrate that component to others.

Problem-Solving

| Components | Building | Enhancing | Proficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identify the Issue to Be Addressed | Recognize familiar problems and the common issues or variables within them. | Identify common variables in new issues and problems, connecting past experience to the problem. | Identify complex and contradictory variables within new and unfamiliar problems and the specific issues at play within them. |

| Gather Information | Connect past experience, knowledge, and skills to familiar problems and common issues. | Identify information sources beyond your past experience that are useful for an unfamiliar issue or problem. | Use new-to-you or complex methods of research to identify information on new-to-you or complex problems. |

| Analyze the Issue | Determine potential common reasons for familiar problems or issues. | Determine multiple causes of and variables of problems and issues that are new-to-you based on gathered information. | Using assessments, tests, research, and external standard procedures analyze a complex issue and synthesize the information about it. |

| Create Multiple Options | Troubleshoot familiar problems or issues by determining options for solutions based on past experience with similar problems and issues. | Troubleshoot and develop multiple choices for solving problems and issues where the causes and variables are knowable but require more than one step to analyze. | Determine multiple options for solutions or decisions about complex problems which have unfamiliar variables or unknown causes based on substantial research or diverse unfamiliar sources. |

| Address the Issue | Determine and implement a decision or solution to common or familiar problems and issues based on past or best practice. | Select and implement the best solution to a complicated problem or issue with multiple variables and causes that were previously unknown to you. | Implement and iterate on solutions and decisions to complex problems where there is no identifiable best choice. |

| Evaluate Effectiveness of Solution | Assess whether past or best practice solutions were effective in resolving a problem or issue. | Assess and evaluate the effectiveness of the solution or decision made to solve a problem according to an external standard. | Assess and evaluate the effectiveness of a complex solution or decision to a complex problem or issue where there is no identifiable best choice. |

Creativity & Innovation

| Components | Building | Enhancing | Proficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use Imagination and Curiosity | Imagine a world in which things are different. | Imagine a world in which things are different and explore what might need to happen for that world to be real. | Imagine a world in which things are different and identify specific changes that could happen to make it a reality. |

| Identify Opportunities to Innovate | Explore new-to-you ideas and understand when others show me how they can be expanded. | Explore new and innovative ideas and identify ways they can be improved or expanded. | Expand and innovate on ideas new-to-you and others in a way that substantially improves them. |

| Generate Ideas That Are New | Generate new-to-you ideas yourself with support and guidance from someone else. | Generate new-to-you ideas without support from others. | Generate new and original ideas others have not considered before. |

| Develop Ideas | Develop ideas within the norms and habits of your environment with support. | Develop ideas while embracing uncertainty or failure without support. | Develop ideas in new, innovative, or original ways that iterate on failures. |

| Apply Ideas | Implement ideas others bring forward into systems you are familiar with. | Implement ideas you and others generate in situations without a correct or knowable answer. | Implement a wide variety of innovations and ideas generated by you and others in new and unique ways that embrace failure as part of the process. |

| Facilitate a Creative and Innovative Environment | Accept changes others make to your environment that are designed to make it more creative or innovative. | Organize your environment in a way that supports your creativity. | Facilitate an environment for others to be creative and innovative. |

Communication

| Components | Building | Enhancing | Proficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Listen With Intention | Actively listen to topics of interest in an attempt to understand the listener rather than simply to develop a response. | Actively listen to many topics outside of interests in an attempt to understand the listener with no intention of developing a response. | Actively listen to topics which are counter to your own interests or biases or know little about in an attempt to understand the listener with no intention of developing a response. |

| Listen to Understand | Understand content on topics of interest presented with factual and concrete language and understand common non-verbal cues. | Understand content on topics outside of interests presented with factual and abstract language or which includes non-verbal or culturally influenced information. | Understand abstract concepts and content with which you disagree or about things which you know little about and able to understand non-verbal or culturally influenced information from cultures other than your own. |

| Speak With Clarity | Speak about topics of interest in a way that others understand your concepts when presented using factual and concrete language. | Speak about topics outside of interests in a way that others understand your concepts when presented using factual and abstract language. | Speak on a wide range of topics in a way others understand even if they do not have the same cultural worldview. |

| Speak With Purpose | Speak about topics of interest in a way that is structured to explain your points to those who know the topic well. | Speak about topics outside of interests in a way that is structured to explain your points to those who know little about the topic. | Structure speaking on a wide range of topics in a way that guides others through learning about the topic so that they come to the same level of understanding as you, even if they knew little to start with. |

| Adapt to My Audiences and Contexts | Present on topics of interest to a single person. | Present on topics of interest to individuals or small groups of people you do not know or in places you are not familiar with. | Present on a wide range of topics to large and small groups as well as individuals in a variety of spaces and formats. |

| Adapt to Others Communication Modes and Tools | Adapt presentations enough to be understood based on common non-verbal cues from those listening. | Adapt presentations to be better understood based on complex non-verbal and cultural cues from those speaking. | Adapt presentations to be best understood and increase persuasiveness based on shifting contexts, spaces, formats, and group sizes. |

Collaboration

| Components | Building | Enhancing | Proficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work Well With Others | Interact with and accomplish goals with familiar people. | Interact with and accomplish goals with unfamiliar people. | Interact with and accomplish goals with large teams of diverse unfamiliar people. |

| Value Diversity and Inclusion | Maintain respectful behaviour towards those who are different from you. | Value diversity and inclusion within your groups and encourage the respectful behaviour of others in the groups. | Value diversity and inclusion of all groups and work toward improving your and others respectful behaviour of groups. |

| Manage Difficult Interactions With Others | Interact with familiar people in a way that minimizes conflict. | Manage difficult interactions with individuals and groups and manage conflicts between others and yourself. | Manage difficult interactions within and between groups and work toward resolving conflicts. |

| Facilitate an Environment of Collaboration | Collaborate with familiar people or small groups of unfamiliar people to complete routine tasks. | Collaborate with familiar people and groups of unfamiliar people to coordinate tasks. | Collaborate with large groups, taking responsibility for coaching, motivating, and evaluating others. |

| Achieve a Common Goal With Others | Work toward a routine goal with familiar people or small groups of unfamiliar people. | Work toward a simple goal with groups of unfamiliar people. | Achieve complex goals with large groups in unpredictable situations. |

| Reflect and Improve on Teamwork | Reflect and improve on how you work with familiar people. | Reflect and improve on how you work with unfamiliar people. | Reflect and improve on how groups of people work together. |

Adaptability

| Components | Building | Enhancing | Proficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demonstrate Responsibility | Follow provided directions responsibly with some supervision. | Follow provided and implied directions with minor supervision. | Independently determine what is expected of you and demonstrate responsibility without supervision. |

| Persist and Persevere | Stay positive and persist in the face of minor changes. | Stay positive, persist, and persevere in the face of moderate changes. | Stay positive, persist, and persevere in the face of complex or substantial changes. |

| Regulate Emotions | Regulate emotions in response to minor stress. | Regulate emotions in response to moderate stress. | Regulate emotions in response to high stress. |

| Set or Adjust Goals and Expectations | Set goals and expectations with direction and adjust in response to minor changes. | Set goals and expectations with supervision and adjust in response to moderate changes. | Set goals and expectations independently and adjust in response to complex changes. |

| Plan and Prioritize | Plan and prioritize tasks and goals when given direction. | Plan and prioritize tasks and goals with some supervision. | Plan and prioritize tasks and goals without any supervision. |

| Seek Self-Improvement | Learn what is required of you with direction. | Determine what type of learning or self-improvement is needed with some supervision and begin working on it. | Identify opportunities for self-improvement and life-long learning independently and progress towards them. |

This assessment was developed by Noah D. Arney (2024) and is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. For more information about this assessment, see the Career Theory and Advising website.

Conclusion

A strong sense of self-awareness is the first step in making informed career decisions. Once you feel you have a strong sense of yourself and your skills, your next step is to expand external awareness. That is to say, learn more about what careers are out there and how viable they may be. The next chapter on Labour Market Information will explore these concepts. In the Career Planning and Goal Setting chapter, you will read about how an awareness of self and available career options can be integrated to make career decisions.

Attribution

This chapter was used and adapted by the authors from 1. Self-Assessment by Mitch Clingo (2023), via University to Career [edited by Jamie Noakes], under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Media Attributions

- Figure 2.1 “Systems Theory Framework of Career” by Wendy Patton and Mary McMahon (1999), via Career Development and Systems Theory: A New Relationship, is used with permission.

- Figure 2.2 “Figure 1. Indigenous Wholistic Framework” by Pidgeon (2016), via “More Than a Checklist: Meaningful Indigenous Inclusion in Higher Education” in Social Inclusion, is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 2.3 “Skills for Success skills wheel” by Employment and Social Development Canada (2024a), via Government of Canada, is used under the Government of Canada Terms and Conditions.

- Figure 2.4 “Holland’s Hexagram” by Linda Turner (2018), via Parental Alienation, is used with permission.

- Figure 2.5 “Big Five Personality Traits – Infographic” [visualized in Adioma; source: “Personality Structure: Emergence of the Five-Factor Model” by J. M. Digman (1990)] by Anna Vital (2018) is used with permission.

- Figure 2.6 “Mental Therapy Counseling” by Mohamed_hassan (2021), via Pixabay, is used under the Pixabay content license.

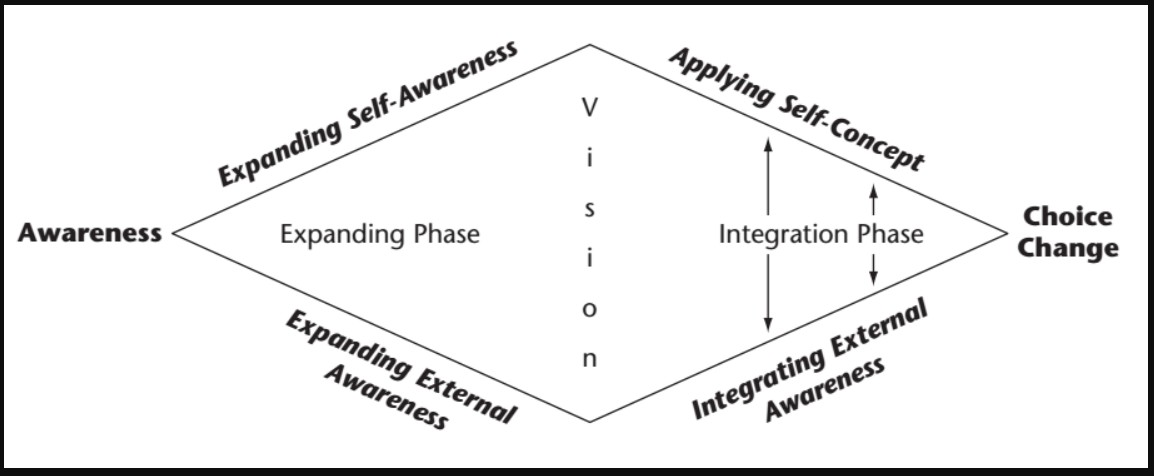

- Figure 2.7 “Career Diamond” [Originally created in Career Counseling and Development in a Global Economy by Andersen and Vandehey, 2006, p. 43.] by Matthew Guruge (2021), via Awato, is used with permission.

References

Arney, N. (2021, May 27). Comparing essential skills frameworks as a tool for career development. CareerWise. https://careerwise.ceric.ca/2021/05/27/comparing-essential-skills-frameworks-as-a-tool-for-career-development/

Arney, N. D. (n.d.). Subjective reports transferable skills assessment. Career Theory and Advising. Retrieved February 9, 2024, from https://careertheory.trubox.ca/srtsa/

Arney, N. D. & Krygsman, H. (2022). Work-integrated learning policy in Alberta: A post-structural analysis. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, (198), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.7202/1086429ar

Burch, G. S. J., & Anderson, N. (2009). In P. J. Corr, & G. Matthews (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personality psychology (pp. 748–763). Cambridge University Press.

Cherry, K. (2022, October 19). What are the big 5 personality traits? Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/the-big-five-personality-dimensions-2795422

Clingo, M. (2023). 1. Self-assessment. In J. Noakes (Ed.), University to career. Thompson Rivers University. https://universitytocareer.pressbooks.tru.ca/chapter/self-assessment/

The Conference Board of Canada. (n.d.). Finding your employability skills. Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://www.conferenceboard.ca/future-skills-centre/tools/finding-your-employability-skills/

Digman, J. M. (1990). Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annual Review of Psychology, 41, 417–440. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.41.020190.002221

Employment and Social Development Canada. (2024a). Learn about the skills. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/services/jobs/training/initiatives/skills-success/understanding-individuals.html

Employment and Social Development Canada. (2024b). Skill components and proficiency levels. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/services/jobs/training/initiatives/skills-success/learning-steps.html

Guruge, M. (2021, April 1). A career counselor’s guide to career assessment. Awato. https://awato.co/career-assessment-guide/

Hidi, S., & Renninger, K., (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_4

Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments (3rd. ed.). Psychological Assessment Resources.

Knowdell, R. (2005). Knowdell motivated skills card sort. Career Research & Testing, Inc.

Lengelle, R. & Meijers, F. (2015). Career writing. In M. McMahon, & M. Watson (Eds.), Career assessment: Qualitative approaches (pp 145–151). SensePublishers.

McIlveen, P., & Patton, W. (2007). Narrative career counselling: Theory and exemplars of practice. Australian Psychologist, 42(3), 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060701405592

Patton, W. & McMahon, M. (1999). Career development and systems theory: A new relationship. Brooks/Cole

McMahon, M., Patton, W., & Watson, M. (2017). From the systems theory framework to my system of career influences: Integrating theory and practice with a black South African male. In L. A. Busacca & M. C. Rehfuss (Eds.), Postmodern career counseling: A handbook of culture, context, and cases (pp. 285–298). American Counseling Association.

McMahon, M. L., Patton, W., & Watson, M. (2017a). My system of career influences – MSCI (adolescent): A qualitative career assessment reflection process: Workbook (2nd ed.). Australian Academic Press.

McMahon, M. L., Patton, W., & Watson, M. (2017b). My system of career influences – MSCI (adolescent): A qualitative career assessment reflection process (2nd ed.). Australian Academic Press.

McMahon, M., & Watson, M. (2019, June 5). Challenges and opportunities in qualitative career assessment. CERIC. https://ceric.ca/2019/06/challenges-and-opportunities-in-qualitative-career-assessment/

McMahon, M., Watson, M., & Lee, M. C. Y. (2019). Qualitative career assessment: A review and reconsideration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110(Part B), 420–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.03.009

McMahon, M., Watson, M., & Patton, W. (2013). My system of career influences MSCI (adult): Facilitator’s guide. Australian Academic Press.

Metz, A. J., & Jones, J. E. (2013). Ability and aptitude assessment in career counseling. In S. Brown, S. & B. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (2nd ed., pp. 449–476). John Wiley & Sons.

Okocha, A. A. G. (1998). Using qualitative appraisal strategies in career counseling. Journal of Employment Counseling, 35(3), 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.1998.tb00996.x

Open-Source Psychometrics Project. (2019). Holland code (RIASEC) test. https://openpsychometrics.org/tests/RIASEC/

Patton, W., & McMahon, M. (2014). Career development and systems theory: Connecting theory and practice. Sense Publishers.

Pidgeon, M. (2014). Moving beyond good intentions: Indigenizing higher education in British Columbia universities through institutional responsibility and accountability. Journal of American Indian Education, 53(2), 7–28. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43610473

Riggio, R. E. (2018, June 6). Does your personality determine your career? Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/cutting-edge-leadership/201806/does-your-personality-determine-your-career

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. Free Press.

Savickas M. L., & Hartung, P. J. (2012). My career story: An autobiographical workbook for life-career success. Retrieved from http://www.marksavickas.com/assessments/

Spokane, A. R., Luchetta, E. J., & Richwine, M. H. (2002). Holland’s theory of personalities in work environments. In D. Brown (Ed.), Career choice and development (4th ed., pp. 373–426). John Wiley & Sons.

Truity. (n.d.). The Big Five personality test. Retrieved February 20, 2025, from https://www.truity.com/test/big-five-personality-test

Viczko, M., Lorusso, J., & McKechnie, S. (2019). The problem of the skills gap agenda in Canadian post-secondary education. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, (191), 118–130. https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/cjeap/article/view/62839

Wille, B., De Fruyt, F. (2014, March). Vocations as a source of identity: Reciprocal relations between Big Five personality traits and RIASEC characteristics over 15 years. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(2), 262–281. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0034917

Long Descriptions

Figure 2.1 Long Description: Starting from the outside, the concentric circles include:

- Past, Present, and Future

- Peers, political decisions, family, historical trends, media, globalization, community groups, socioeconomic status, workplace, employment market, education institution, and geographical institution.

- Individual: Gender, values, sexual orientation, interests, skills, age, physical attributes, aptitudes, world of work knowledge, ethnicity, self-concept, personality, disability, health, gender, and ability.

Three lightening bolts start in the innermost circle and end at the outermost circle.

Figure 2.2 Long Description: Starting from the outside, the concentric circles include:

- Reciprocity, Relevance, Responsibility, and Respect

- Community and Nation

- Family

- Individual

There are also arrows pointing to the centre labelled Physical, Intellectual, Spiritual, and Emotional.

Figure 2.4 Long Description: Psychologist Holland divided personality types into a 6-factor typology. With a few keywords for each, they are:

- Investigative: structured, organized, and careful

- Artistic: expressive, creative and visual

- Social: helping, empathetic, communicative and friendly

- Enterprising: influential, energetic, sociable, and leader

- Confidential: structured, organized and careful

- Realistic: practical, hands-on, and tangible work

Figure 2.5 Long Description: J. M. Digman’s Personality Structure: Emergence of the Five-Factor model is described as follows:

- Conscientiousness: A tendency to be organized and dependable; ranging from efficient and organized to easy-going and careless

- Extraversion: A tendency to seek the company of others and talk; ranging from solitary and reserved to outgoing and energetic

- Agreeableness: A measure of one’s trusting and helpful nature; ranging from challenging and detached to friendly and compassionate

- Neuroticism: Predisposition to psychological stress; ranging from secure and confident to sensitive and nervous

- Openness: Degree of intellectual curiosity, creativity and a preference for novelty; ranging from inventive and curious to consistent and cautious

Figure 2.7 Long Description: This framework illustrates that a person begins their career confused and unaware about who they are, the job market, or both. The process of career counseling helps them expand their knowledge and then find some resolution about both to make a career choice or change.

The person begins when they are aware they need to explore careers and make a choice in the world of work. The top of the diamond represents the person’s self-awareness; it expands and then narrows down to an eventual choice or change. The bottom of the diamond is the person’s awareness of the world of work, which expands and then narrows to a choice.

On one side of the diamond is the Exploring Phase, where a person explores their own internal self-concept and expands their external awareness of the work world. The other side is the Integration Phase, when the person applies their self-concept and integrates it with their new knowledge (external awareness) of the work world.