11. Experience More Access

Jennifer Mei

Introduction

This chapter discusses:

- Why it is important to know what health conditions are considered a disability

- How our values and upbringing influence our idea of disability

- Ways to highlight our strengths

- Strategies for disclosing a disability to an employer

This knowledge will help us create an accessible workplace that includes and supports everyone. It is a big topic, and not everything can be covered in this short chapter, but it is a starting point to understanding why it is a good idea to find out everything we can about how to set ourselves up for success.

Sometimes, there are a lot of steps to getting the help you need to be successful in the workplace. Also, it is important to note that the help you needed in school may be different or unnecessary in your work environment. For example, you may have needed extra time to write your final exam in school, but you might not need that accommodation in a job that does not require you to write exams. This chapter provides tools to help you figure out what kind of support you need.

One of the theories that guide this chapter recognizes that everyone is different and there is no one-size fits all approach to providing people with what they need (Barile, 2002, p. 2). In academic terms, this is referred to as anti-oppressive theory (Brown & Strega, 2015, p. 39). The other theory that guides this chapter helps us recognize what we can bring to the table with the right support. This is referred to as strength-based theory, which suggests that focusing on what we are good at can change the way employers see us as well as how we see ourselves.

It is also important that we have a good understanding of what health conditions employers consider a disability if we would like to ask them for support. Doctors and other medical professionals use the term disability to describe a permanent or temporary health condition that makes it more challenging for a person to work and learn in a “typical” way. Different industries will likely have different ways of defining what they think the “typical” ways are of doing things.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapters, you should be able to:

- Describe how our values and upbringing influence our ideas of disability.

- Identify health conditions medically considered a disability.

- Identify ways a health condition can affect the way people work and learn.

- Explain how a universal design creates an accessible environment for everyone.

- Use strength-based language to describe what you can do with the right support.

Understanding Disability

Why Does Disability Matter in the Workplace?

Depending on our upbringing and values, we may not think of our physical or mental differences as a disability (Stroman, 2003, p. 209). It is possible for us to honour our own cultural perspectives on disability while respecting the views of others. We have much to learn about the different ways people feel about their health and well-being and the best way to create safe workplace environments for everyone.

Canadian employers often use the medical idea of disability to make a decision about a person’s need for support or accommodations in the workplace. (Robertson & Larson, 2016, p. 59). That is why it is important to know as much as we can about their perspective so that we can advocate for what we need to do our best work. According to the Centers of Disease Control (2020), “ A disability is any condition of the body or mind (impairment) that makes it more difficult for the person with the condition to do certain activities (activity limitation) and interact with the world around them (participation restrictions).”

People may prefer to use other terms to describe temporary or ongoing conditions, such as diversability, different abilities, injury, illness, diagnosis, stress and chronic pain, to name a few. This chapter will use these terms interchangeably to describe health conditions that impact a person’s mental and physical functioning.

Reflection

Your Experience With Disability

- When you were a kid, what did you know about physical and mental health disabilities?

- How do you think your values, beliefs, and upbringing influenced your idea of disability?

- What kind of help was available for people who had disabilities and/or struggled with mental health?

- What do you believe about disability as an adult? What has changed?

How Common are Disabilities?

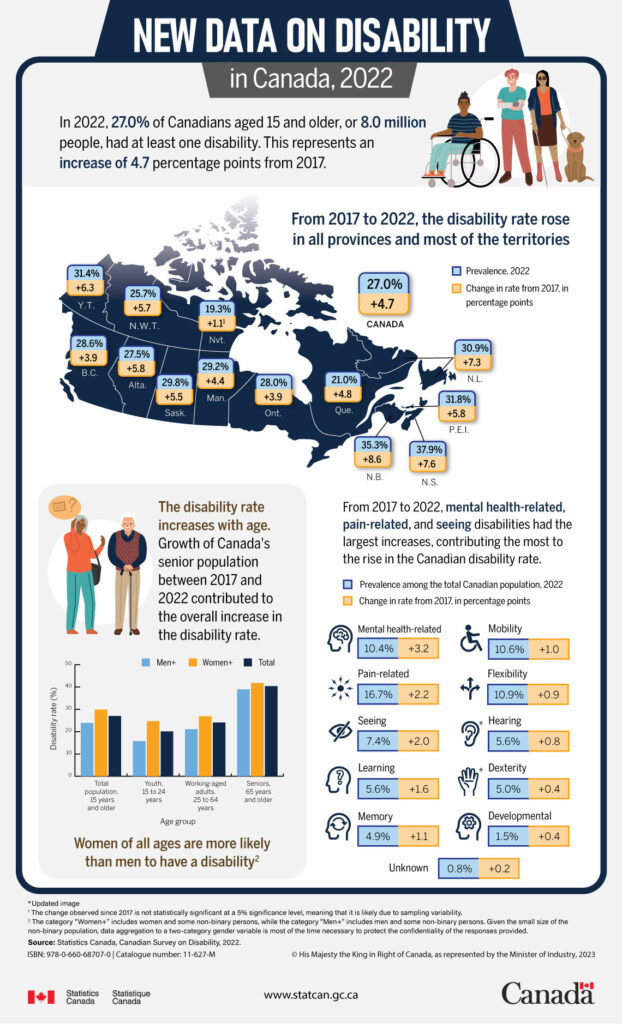

The latest information from Statistics Canada (2023) shows that the number of people with disabilities has increased from 2017 to 2022 (Figure 11.3). This includes non-apparent disabilities like mental health. If we want to create a workplace that includes everyone, we will need to remember that we might not know if someone has a non-apparent disability and continue to treat our co-workers as valued members of our teams.

Different Kinds of Disabilities

Employers will often rely on the assessment and recommendations of a doctor, specialist, and/or other healthcare professional to make decisions about eligibility for workplace accommodations. Medical professionals may attribute a person’s diagnosis to the area most affected by their symptoms. Descriptions for these different types of disabilities are outlined in this section.

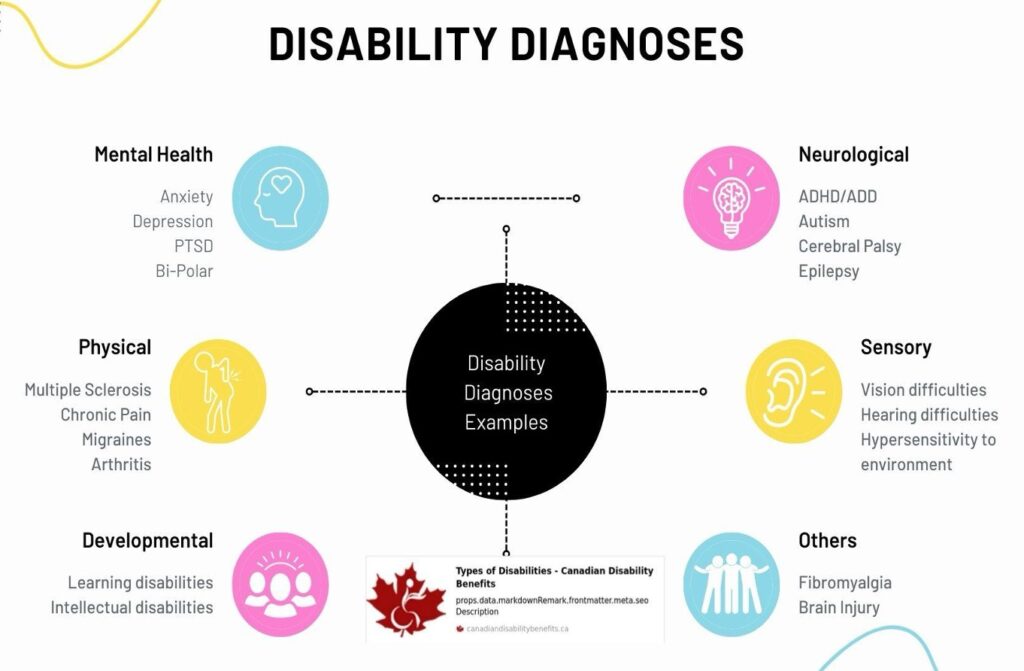

Disabilities are usually categorized by type. Figure 11.5 below gives a general idea of what kinds of disabilities are out there and the employability traits that might come along with a diagnosis.

Note. Figure 11.5 reflects the common Western medical view of disability and does not intend to replace people’s freedom to approach health and wellness from their own cultural perspectives and ways of knowing. There is a lot of stigma surrounding the term disability, and some people prefer to avoid it all together.

Knowing what type of disability we have can help with determining ways our working and learning environments can be set up to give us the best outcomes. Now that we have identified different types of disabilities, let’s explore what conditions may be considered a disability from a Western medical perspective.

Health Conditions Considered a Disability

Whether temporary or permanent, disabilities can impact people unexpectedly. For example, a person may experience a car accident or sports injury that changes how they move about and experience the world; these changes can include difficulties with mobility, chronic pain, fatigue, or distress. In these instances, people may need to request temporary or permanent accommodations to support the new ways they work and learn. Figure 11.6 gives just a few examples of what might be considered a disability that may require accommodations in the workplace. This is not a complete list, but you can find out more about conditions considered disabilities on the Canadian Disability Benefits (n.d.) website.

Humans also age, and aging may come with various levels of physical and mental health challenges. Changing our outlook on disability—whether acquired, genetic, or naturally occurring—could open further education and employment opportunities if we know we can be successful with right support in place. Now that we have a better idea of what diagnoses may be considered a disability, let’s discuss how accommodations can help set us up for academic and workplace success.

Academic & Workplace Accommodations

What are Accommodations?

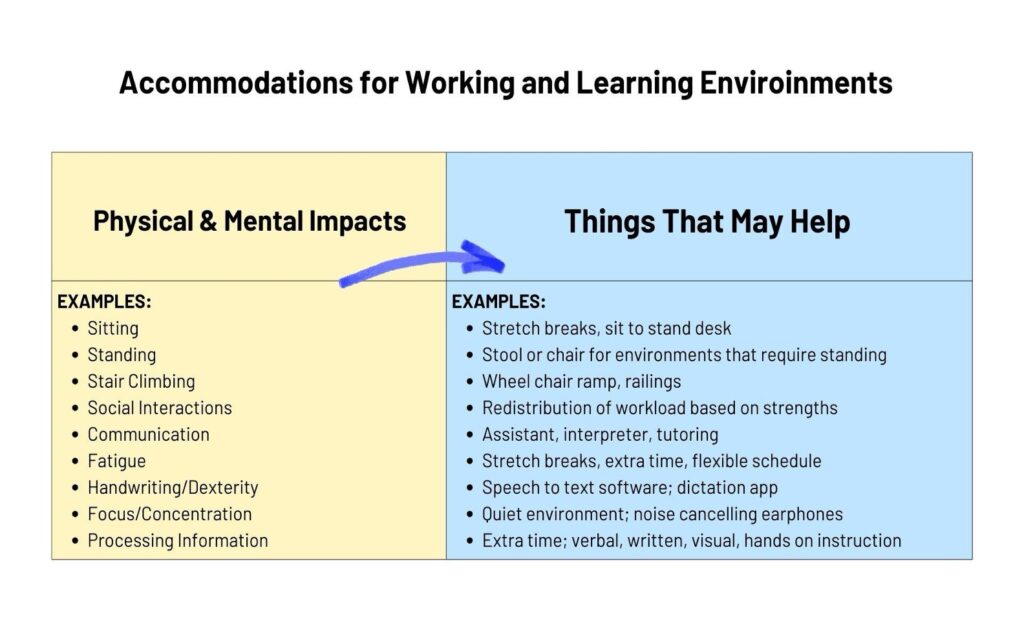

Accommodations are adaptations made to a working and learning environment that help people with health conditions or disabilities meet the essential requirements of their job or educational program (Figure 11.7). This can include changes to our schedule, workload distribution, or physical environment. The way people are impacted by their condition may be different, which means that accommodations can vary from person to person. Some people with diagnoses may need accommodations, while others with the same diagnoses may not, depending on the level of mental or physical coping strategies they have learned over time.

People with disabilities have a legal right to accommodations as per the BC Human Rights Code (1996) and the Accessible Canada Act (2019). Make sure to read through your employer or educational institution’s accessibility policy for steps to accessing accommodations and what to do if you would like to appeal a decision. More information about legal rights to accommodations can be found on the TRU Career and Experiential Learning’s (n.d.b) Career Equity Resources page.

Exploring Learning Styles

Regardless of whether or not you have a disability, everyone works and learns in different ways. Knowing the ways you work best will help us identify the kinds of working and learning environments that suit our strengths. This exercise will give you a visual of the kind of learner you are: Learning Style Questionnaire (LearningStyleQuiz.com, n.d.).

Reflection

Learning Style Questionnaire

- Based on your results, how would you best receive instructions from an instructor or employer?

- What kinds of jobs do you think would best suit your learning style?

- If you have a disability, what are the ways it impacts the way you work and learn?

- What accommodations do you think you would need to request to set you up for success?

This Self Evaluation Tool (TRU Career and Experiential Learning, n.d.a) may also help you think about the kinds of accommodations that would best suit your needs.

Understanding the ways we learn gives us additional knowledge to self-advocate for what we need in the classroom or workplace to set ourselves up for success. Now that we have explored how learning styles and functioning relate to workplace and academic accommodations, let’s move on to why we need accommodations in the first place.

Why Do We Need Accommodations?

Depending on where we live in the world, societies may create a standard set of policies, laws, and systems that everyone is expected to follow. While we need systems to organize ourselves, not everyone is able to navigate these societal expectations in the same way. Many companies and educational institutions incorporate this standard way of doing things into their everyday operations, which can cause challenges for people who have different ways of working and learning. That is why some people need adaptations to level their access to employment and education. This idea is often described using the terms “equity” or “equitable” to indicate that sometimes adjustments are needed to ensure everyone gets the same chance to succeed.

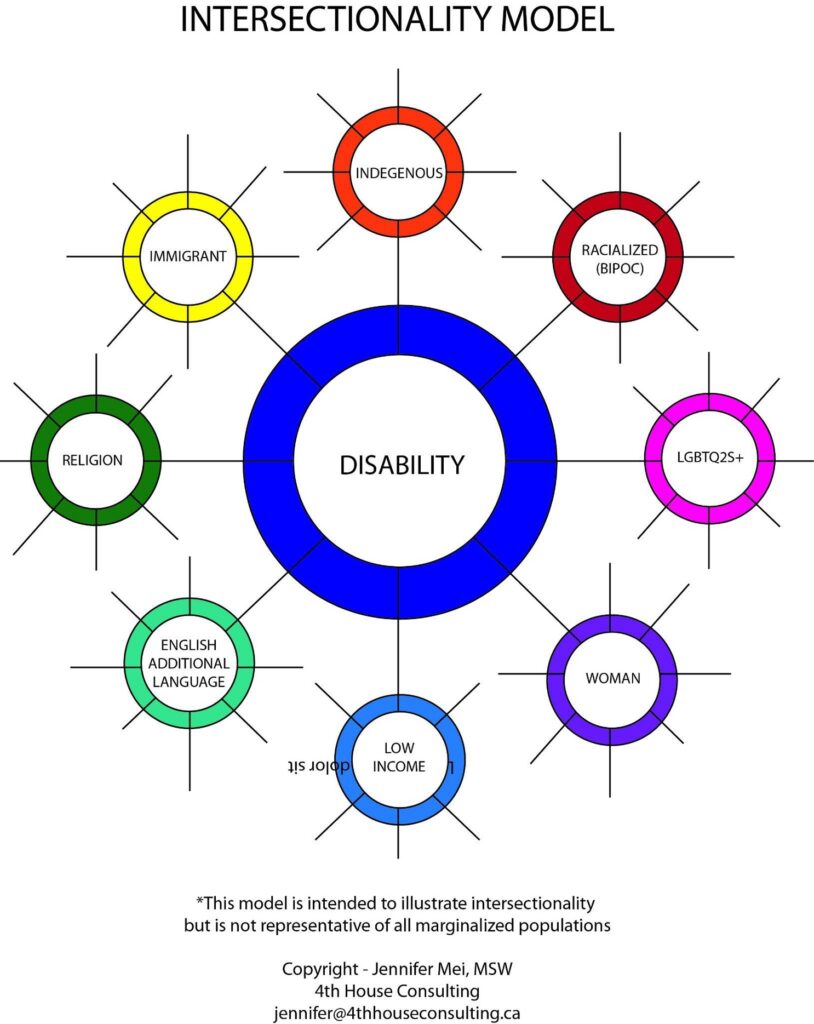

In Western society, more complex challenges can arise for people who have more than one difference that does not fit within the expectations of our society. This can happen for those of us from different cultures or lived experiences who view our health and well-being in ways other than what is considered standard (Collins & Bilge, 2016). Kimberlee Crenshaw, an American civil rights activist, professor, and legal scholar, coined the term “intersectionality” to explain the idea that people’s differences and commonalities can intersect, making it easier or more difficult for individuals to achieve equitable access to employment or education (Cooper, 2016). Figure 11.8 provides a visual representation of intersectionality.

Knowing how our similarities and differences affect how easy or hard it can be to navigate society’s rules can help us identify multiple resources that may support equitable access to education and employment.

Asking for Accommodations

Disclosing Your Disability

Some people may feel that disclosing the nature of their disability will help their employer or instructor understand how to best work with them. However, we are not required to share any medical information about ourselves if we feel unsafe to do so. This includes the specific condition a person is diagnosed with. The amount of information you would like to share in an academic or employment environment is a personal choice. If a person would like to disclose, it is recommended that they find out the right employee or department to speak to about accessibility.

Getting Asked for Medical Documentation

Your employer may ask you for medical documentation to support an accommodation. Make sure to clarify which healthcare professionals are considered qualified to provide this information. Examples of certified healthcare professionals include:

- Family physician

- Specialist

- Psychiatrist

- Audiologist

- Optometrist

- Surgeon

Keep in mind that some medical professionals charge a fee to fill out forms. Documentation from certain healthcare professionals—such as a naturopathic doctor, counselor, nurse, social worker, or physiotherapist—may not be considered valid medical documentation because these clinicians are unable to confirm the presence of a clinical diagnosis.

Visiting Your Medical Professional

When asking your healthcare professional to provide documentation, ask that they include:

- Information about how your disability impacts your functioning

- Recommendations for your accommodation(s)

- Confirmation of a diagnosed disability/health condition

Using a Strength-Based Approach

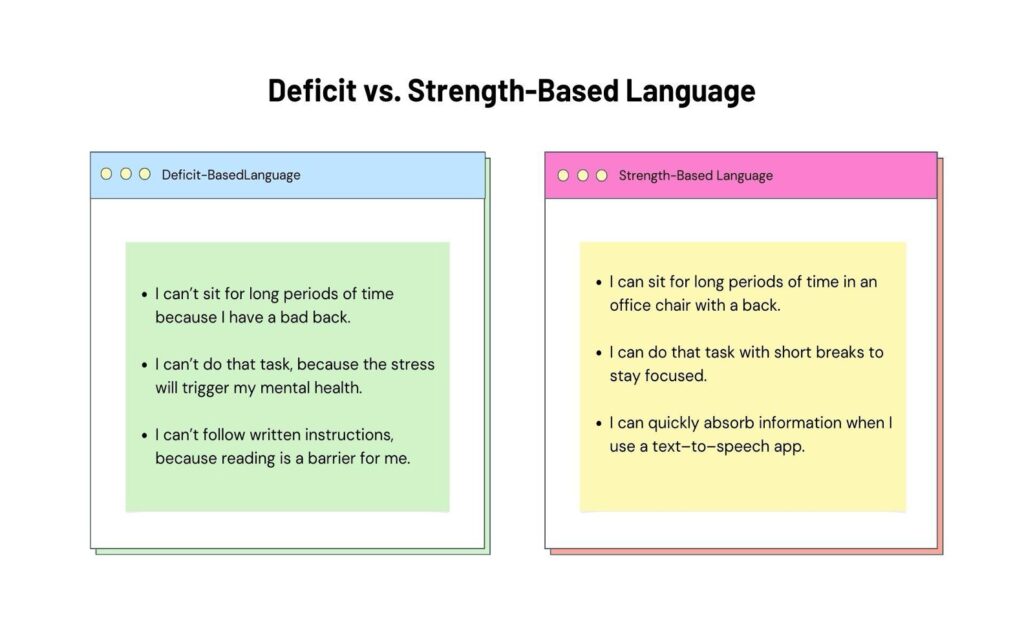

Using a strengths-based approach to requesting accommodations shows the employer that a person is capable and qualified for the job. Disclosing a disability is not necessary in an informational interview, employment interview, cover letter, or resume. However, it is important to notice how we speak about ourselves. Sometimes, we unconsciously use negative or deficit-based language to describe our skills and abilities (University of Michigan, n.d.). Figure 11.9 shows the contrast between using deficit-based and strengths-based language.

Tip. When presenting yourself during the job search process, remember your unique abilities may positively set you apart from other candidates. Using a strengths-based perspective, focus on why you believe you are capable and qualified for the job.

Reflection

Deficit-Based vs. Strength-Based

- How would you change the following statements from deficit-based to strength-based?

- I do not understand verbal instructions.

- I cannot stand for long periods of time.

- I have trouble with time management.

- I do not understand social cues or interactions.

- I cannot focus or concentrate on my work sometimes.

- Are there ways you could change the language you use to describe your own situation to be more strengths-based?

What Are My Rights?

Legislation

People with disabilities have the right to equal access to employment (Canadian Human Rights Commission, 2015), which includes workplace accommodations if needed. According to the BC Human Rights Code (1996):

A person must not, without a bona fide and reasonable justification, deny to a person or class of persons any accommodation, service, or facility customarily available to the public, or discriminate against a person or class of persons regarding any accommodation, service, or facility customarily available to the public because of the race, colour, ancestry, place of origin, religion, marital status, family status, physical or mental disability, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or age of that person or class of persons (Section 8[1]).

Tip. If you feel your employer has not honored this right, you may choose to make a formal complaint. If so, make sure to document your experiences and review your company’s policy on the complaint process. Then, follow the steps required to get your complaint heard. If you need assistance with the process, contact your designated human resources officer for support. It is important to understand your human rights and what to expect if your complaint is not resolved internally. You may choose to take your case to the BC Human Rights Tribunal (n.d.).

Further Reading

- BC Human Rights Code (1996)

- BC Human Rights Tribunal (n.d.)

- BC Human Rights Clinic (n.d.)

Universal Design: Access for Everyone

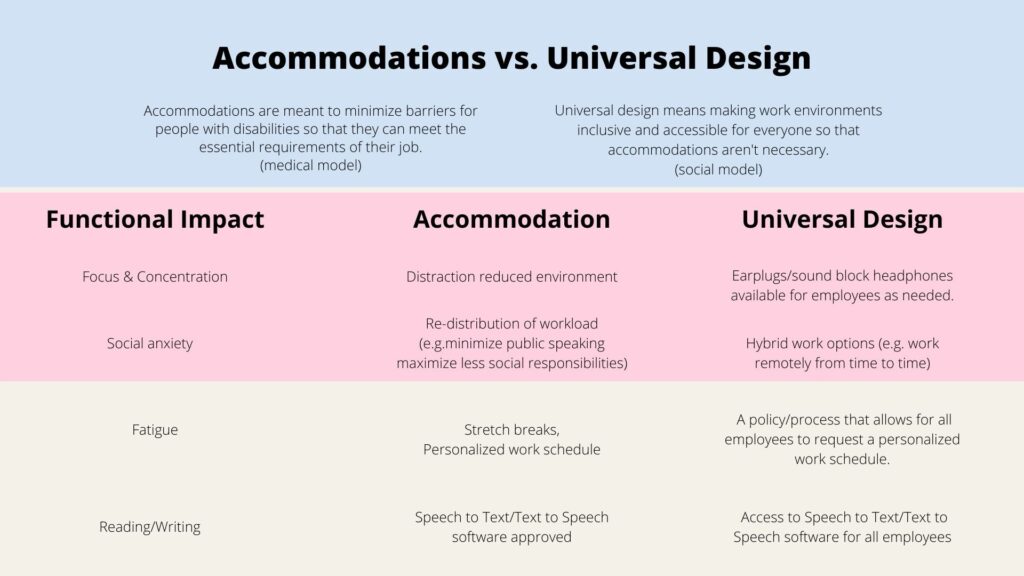

Universal design is the idea that we can make workplaces and classrooms accessible for everyone. Depending on current policies and procedures, some workplaces or classrooms may be more ready than others to make a shift in this direction. However, there may be some simple ways that employers and educators can start making working and learning environments more inclusive. For example, earplugs could be made available to all employees in a workplace that has lots of distractions or for students writing an exam. Universal design reduces the need for accommodations because the environment is already accessible (Figure 11.10).

Now that we have explored ways to make working and learning environments more accessible for everyone, let’s learn more on how we can be even more inclusive as colleagues and classmates.

Allyship

Allyship is a gift.

If a person discloses that they have a disability, approach the topic with curiosity. People who have disabilities are the best ones to tell you what it is like. In Understanding Disability, we discussed how our values, culture, and upbringing influences our understanding of disability. It is important to reflect on your biases and beliefs about disability before making assumptions about the person’s experience.

It is also important to note that allyship is gifted to the person who does not have experience living with a disability. The person vulnerable to discrimination chooses who they feel safe discussing their lived experiences with. This includes people with intersectional experiences (see Figure 11.8).

Conclusion

Living with a condition that impacts your functioning is not always easy, especially when it comes to equitable access to employment or education and requesting accommodations. The information provided in this chapter is intended to provide information and practical tools to help people navigate a system that does not always make sense.

To better understand the importance of accessibility, we discussed how values influence our ideas about disability, identified conditions that may be considered a disability, explored our learning styles, developed strategies for requesting accommodations, learned ways universal design can benefit everyone, and gained a better understanding of allyship. This knowledge is intended to broaden opportunities and create accessible environments for people with diverse lived experiences and needs.

Media Attributions

- Figure 11.1 “People Having a Meeting at the Office” by Kampus Production (2020), via Pexels, is used under the Pexels License.

- Figure 11.2 “Woman in White and Black Top Using Computer” by fauxels (2019), via Pexels, is used under the Pexels License.

- Figure 11.3 “New data on disability in Canada, 2022 [Catalogue No. 11-627-M]” by Statistics Canada (2023) is used under the Statistics Canada Open Licence.

- Figure 11.4 “Young lady learning sign language during online lesson with female tutor” by SHVETS production (2021), via Pexels, is used under the Pexels License.

- Figure 11.5 “Disability types” by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 11.6 “Disability diagnoses” by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 11.7 “Accommodations for working and learning environments” by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 11.8 “Intersectionality model” by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 11.9 “Using strength-based language” by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 11.10 “Accommodations vs. Universal Design” by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

Accessible Canada Act, SC 2019, c 10. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/a-0.6/

Barile, M. (2002). Individual-systemic violence: Disabled women’s standpoint. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 4(1), Article 1. https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol4/iss1/1/

BC Human Rights Clinic. (n.d.). Home. https://bchrc.net/

BC Human Rights Tribunal. (n.d.). Home. http://www.bchrt.bc.ca/

Brown, L. A., & Strega, S. (Eds.). (2015). Research as resistance: Revisiting critical, indigenous, and anti-oppressive approaches (2nd ed.). Canadian Scholars Press.

Canada Disability Benefits (n.d.). Types of disabilities. Retrieved February 19, 2025, from https://canadiandisabilitybenefits.ca/types-of-disabilities/

Canadian Human Rights Commission. (n.d.) Employment Equity Act responsibilities. https://www.chrc-ccdp.gc.ca/eng/content/employer-obligations

Canadian Humans Right Commission. (2015). The rights of persons with disabilities to equality and non-discrimination: Monitoring the implementation of the UN Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in Canada (Catalogue No. HR4-29/2015E-PDF). Government of Canada. https://publications.gc.ca/pub?id=9.805656&sl=0

Centers for Disease Control and Protection (2020). Disability and health overview. https://www.cdc.gov/disability-and-health/about/index.html

Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2016). Intersectionality. Polity Press.

Cooper, B. (2016). Intersectionality. In L. Disch & M. Hawkesworth (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of feminist theory (pp. 385–406). Oxford University Press.

Human Rights Code, RSBC 1996, c. 210. https://www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/00_96210_01 (This Act is current to March 1, 2023)

LearningStyleQuiz.com. (n.d.). What is your learning style? https://learningstylequiz.com/

Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction. (2022). Persons with disabilities designation application (HR2883) [PDF]. Government of British Columbia. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/british-columbians-our-governments/policies-for-government/bc-employment-assistance-policy-procedure-manual/forms/pdfs/hr2883.pdf

Mont, D., & Loeb, M. (2010). A functional approach to assessing the impact of health interventions on people with disabilities. Alter, 4(3), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alter.2010.02.010

Pardo, P., Student and Academic Services, & Tomlinson, D. (1999). Implementing academic accommodations in field/practicum settings (U15925204). University Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary. https://digitalcollections.ucalgary.ca/asset-management/2R3BF1FNBBPP9

Piepzna-Samarasinha, L. L. (2018). Care work: Dreaming disability justice. Arsenal Pulp Press.

Robertson, J., & Larson, G. (2018). Disability and social change: A progressive Canadian approach. Fernwood Publishing.

Simler, C. (2020, July 9). 30 examples of workplace accommodations you can put into practice. Understood. https://www.understood.org/en/articles/reasonable-workplace-accommodation-examples

Statistics Canada. (2018). New data on disability in Canada, 2022 (Catalogue No. 11-627-M). Government of Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2023063-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2023). New data on disability in Canada, 2022 (Catalogue no. 11-627-M) [Image]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2023063-eng.htm

Stroman, D. F. (2003). The disability rights movement: From deinstitutionalization to self-determination. University Press of America.

TRU Career and Experiential Learning. (n.d.a). Accommodations self assessment template [PDF]. Thompson Rivers University. https://www.tru.ca/__shared/assets/accommodations-self-assessment-template52641.pdf

TRU Career and Experiential Learning. (n.d.b). Career Equity Resources. Thompson Rivers University. https://www.tru.ca/cel/career-equity-resources.html

University of Memphis. (n.d.). Module 4: Asset based community engagement – U of M’s urban-serving research mission. https://www.memphis.edu/ess/module4/

Washington, E. F. (2022, May 10). Recognizing and responding to microaggressions at work. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2022/05/recognizing-and-responding-to-microaggressions-at-work

World Health Organization. (2001). International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/

Long Descriptions

Figure 11.3 Long Description: In 2022, 27% of Canadians aged 15 and older, or 8 million people, had at least one disability. This represents an increase of 4.7 percentage points from 2017.

From 2017 to 2022, the disability rate rose in all provinces and most of the territories:

| Province/Territory | Prevalence, 2022 | Change in Rate From 2017, in percentage points |

|---|---|---|

| Canada | 27% | +4.7 |

| Alberta | 27.5% | +5.8 |

| British Columbia | 28.6% | +3.9 |

| Manitoba | 29.2% | +4.4 |

| New Brunswick | 35.3% | +8.6 |

| Newfoundland & Labrador | 30.9% | +7.3 |

| Northwest Territories | 25.7% | +5.7 |

| Nova Scotia | 37.9% | +7.6 |

| Nunavut | 19.3% | +1.1 |

| Ontario | 28% | +3.9 |

| Quebec | 21% | +4.8 |

| Prince Edward Island | 31.8% | +5.8 |

| Saskatchewan | 29.8% | +5.5 |

| Yukon | 31.4% | +6.3 |

The disability rate increases with age. Growth of Canada’s senior population between 2017 and 2022 contributed to the overall increase in the disability rate.

Women of all ages are more likely than men to have a disability:

| Age Group | Men+ | Women+ | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total population, 15 years and older | 23.9% | 29.9% | 27% |

| Youth, 15 to 24 years | 15.8% | 24.7% | 20.1% |

| Working-Age Adults, 25 to 64 years | 21.1% | 26.9% | 24.1% |

| Seniors, 65 years and over | 38.9% | 41.8% | 40.4% |

From 2017 to 2022, mental health-related, pain-related, and seeing disabilities had the largest increases, contributing the most to the rise in the Canadian disability rate.

| Disability Type | Prevalence Among the Total Canadian Population, 2022 | Change in Rate From 2017, in percentage points |

|---|---|---|

| Mental Health-Related | 10.4% | +3.2 |

| Pain-Related | 16.7% | +2.2 |

| Seeing | 7.4% | +2 |

| Learning | 5.6% | +1.6 |

| Memory | 4.9% | +1.1 |

| Mobility | 10.6% | +1 |

| Flexibility | 10.9% | +0.9 |

| Hearing | 5.6% | +0.8 |

| Dexterity | 5% | +0.4 |

| Developmental | 1.5% | +0.4 |

| Unknown | 0.8% | +0.2 |

Figure 11.5 Long Description: Disability types include:

-

- Mental Health: Mental health can be unpredictable. Therefore, a person with a mental health condition may require workplace flexibility.

- Physical Health: A person with a physical health condition may require adaptations to make a person’s physical work environment safe.

- Developmental: People with developmental differences, like learning, may bring new communication strategies to the workplace.

- Neurological: People who are neurodiverse or neurodivergent, like having autism, may bring innovative problem-solving skills to specific industries.

- Sensory: People with different sensory abilities, like hearing, can meet the expectations of their job with available technology if needed.

- Others: A person’s diagnosis may also fall into more than one category or a different medical category not listed here.

Figure 11.6 Long Description: Disability diagnoses for each disability type include:

- Mental Health: Anxiety, depression, PTSD, and bi-polar.

- Physical: Multiple sclerosis, chronic pain, migraines, and arthritis.

- Developmental: Learning disabilities and intellectual disabilities.

- Neurological: ADHD/ADD, autism, cerebral palsy, and epilepsy.

- Sensory: Vision difficulties, hearing difficulties, and hypersensitivity to environment.

- Others: Fibromyalgia and brain injury.

| Physical and Mental Impacts | Things That May Help |

|---|---|

| Sitting | Stretch breaks; a sit to stand desk |

| Standing | Stool or chair for environments that require standing |

| Stair climbing | Wheel chair ramp; railings |

| Social interactions | Redistribution of workload based on strengths |

| Communication | Assistant; interpreter; tutoring |

| Fatigue | Stretch breaks; extra time; a flexible schedule |

| Handwriting/Dexterity | Speech to text software; a dictation app |

| Focus/Concentration | Quiet environment; noise-cancelling earphones |

| Processing information | Extra time; verbal, written, visual, or hands on instruction |

| Deficit-Based Language | Strength-Based Language |

|---|---|

| I can’t sit for long periods of time because I have a bad back. | I can sit for long periods of time in an office chair with a back. |

| I can’t do that task because the stress will trigger my mental health. | I can do that task with short breaks to stay focused |

| I can’t follow written instructions because reading is a barrier for me. | I can quickly absorb information when I use a text-to-speech app. |

Figure 11.10 Long Description:

Accommodations are meant to minimize barriers for people with disabilities so that they can meet the essential requirements of their job (medical model).

Universal design means making work environments inclusive and accessible for everyone so that accommodations aren’t necessary (social model).

| Functional Impact | Accommodation | Universal Design |

|---|---|---|

| Focus and concentration | Distraction-reduced environment | Earplugs/sound block headphones available for employees as needed |

| Social anxiety | Redistribution of workload (e.g., minimize public speaking and maximize less social responsibilities) | Hybrid work options (e.g., work remotely from time to time) |

| Fatigue | Stretch breaks; personalized work schedule | A policy/process that allows for all employees to request a personalized work schedule |

| Reading/Writing | Speech-to-text/text-to-speech software approved | Access to speech-to-text/text-to-speech software for all employees |