1. Foundations of Career Theory

Shawn Read

Introduction

Throughout my career as a career educator, I have been somewhat ambivalent about the rigid application of career theories without considering the unique circumstances and lived experiences of individuals. While I certainly recognize the value of these theories in providing structure and guidance, I have also observed their effectiveness can be limited when applied in a one-size-fits-all manner. Career development is deeply personal and influenced by a myriad of factors, including cultural background, socioeconomic status, family dynamics, and chance events, which are not always fully accounted for in traditional theoretical frameworks.

With this in mind, I like to think of career theories as tools in a toolbox, each offering a unique way to approach career planning and decision-making. Just as a carpenter selects the right tool for a specific job, job seekers can use these theories to better understand their strengths, interests, and the opportunities available to them. For example, Holland’s theory of vocational choice might help identify careers that align with one’s personality type, while Super’s life-span, life-space theory provides insight into how career goals evolve as individuals grow and take on different life roles. Similarly, Krumboltz’s happenstance learning theory encourages individuals to stay open to unexpected opportunities and adapt to changes in the job market. When used thoughtfully, these theories can serve as valuable guides in navigating the complexities of career development.

As Sharma (2016) aptly states, career “theories and research describing career behaviour provide the conceptual glue,” offering the foundational underpinnings needed to understand how and why these theories should be applied in the job planning process. In today’s rapidly evolving global landscape, career decision-making has become an increasingly intricate and multifaceted endeavor. The modern workforce is shaped by technological advancements, economic shifts, and cultural transformations, which have disrupted traditional career pathways. Individuals are no longer confined to linear or predictable trajectories but must instead navigate a complex web of opportunities, challenges, and uncertainties. In this dynamic environment, career theories provide essential frameworks for interpreting these changes, equipping individuals with the tools to make informed decisions that align with their skills, interests, values, and aspirations. By grounding career planning in established theoretical perspectives, individuals can better address the complexities of contemporary career development, ensuring their decisions are both strategic and adaptable to the demands of an ever-changing world. Together, these theories act as both a compass and a map, helping job seekers chart a course through the uncertainties of the modern career landscape.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Investigate and describe a variety of career theories and how they differ in scope and application.

- Evaluate different career development theories and models in terms of assumptions, accessibility, strengths, limitations, and applications to multicultural contexts.

- Apply theories as an approach to navigating and supporting your individual life-long learning career goals

What is Career Theory?

Career development theories are frameworks that offer a variety of perspectives and principles that may be used to guide an individual’s journey through the complexity of the career planning process. Lent, Brown and Hackett (2002) suggest that career theory attempts to explain how individuals make decisions regarding their career choices, navigate career transitions, and develop a sense of identity and fulfillment through work. While career theories are varied in their approach, it is important for job seekers to have a foundational understanding of these theories to gain insight into career development and factors that align with their traits, personality types, interests, values, cultural contexts, and global changes in our modern world.

Many career theories that we will review are grounded in pedagogies that have been developed and built upon one another over the past 100 years. These theories have responded to significant shifts in changes to the labour market, globalizations of labour, societal adjustments, and expectations in the workforce. As a result of these shifts, theories have evolved from linear trait-focused frameworks, which were common in the 20th century, to more dynamic and holistically focused ideals that address the diversity of an individual’s career experience in contemporary society.

When utilized correctly, career theories may be applied as a piece of a puzzle that helps individuals understand how their skills and abilities may relate to future career planning. It is not, however, a magic wand that will provide individuals with crystal clear occupational choices and a direction for what a person may do for the rest of their life.

Career development is a dynamic and multifaceted process that has intrigued researchers, practitioners, and individuals for decades. This chapter will explore a variety of career theories, examining their principles and implications for understanding and navigating contemporary careers. This chapter will culminate by focusing on two influential perspectives: planned happenstance (Krumboltz & Levin, 2004) and the chaos theory of careers (Bright & Pryor, 2005), which have gained prominence in recent years due to the dynamic changes within the labour market. As we explore career theory in this chapter, we want to stress that no one theory is superior to another and each theory we will review offers different perspectives and approaches, even though you will undoubtedly identify many similarities within these concepts.

Understanding Traditional Career Theories: An Overview

Career development has long been a subject of interest and study, with various theories emerging to explain the process of career choice, development, and success. As Jena and Nayak (2020) highlight, “understanding these theories is an essential step in determining the strengths, weaknesses, fundamental values, and desirable path that are operative while choosing career.” Over the past century, society has witnessed a swift evolution of society—transitioning through industrial, technological, and digital ages—while intertwining global economies.

The study of career development has been significantly enriched by the insights offered by scholars such as Parsons, Holland, Super, and Hackett, to name a few. Many traditional theories suggest that individuals are most satisfied and successful in careers that align with their personality type, skills, interests, and values. These structured frameworks have been incredibly helpful for individuals to make sense of factors influencing career decisions and to offer guidance for the career planning process.

While these theories have undoubtedly shed light on critical aspects of career development, it is essential to acknowledge that they reflect the socioeconomic contexts in which they were formulated. As McMahon and Patton (2002) suggest, the traditional approach to systems theories need to be understood in the context of time and place. In the early part of the last century, the world of work essentially provided individuals with a job for life, but this is no longer the case. Instead, we now understand that as the economy and job market continually evolve, contemporary career theories must adapt to encompass the dynamic nature of work and ensure their relevance.

In the TEDx video below, Sharon Belden Castonguay discusses how career choices are influenced by various factors that impact our career decisions.

The Psychology of Career Decisions | Sharon Belden Castonguay | TEDxWesleyanU [12:26 min] by TEDx Talks (2018)

If you are using a printed copy, you can scan the QR code with your digital device to go directly to the video: The Psychology of Career Decisions | Sharon Belden Castonguay | TEDxWesleyanU

Parsons’ Trait & Factory Theory

Frank Parsons’ (1909) seminal work on trait and factor theory stands as one of the earliest career development theories from the early 20th century. His pioneering work not only established a solid groundwork for countless scholars, career professionals, and job seekers but also continues to influence contemporary career practices today. Notable scholars influenced by Parsons include Donald Super and John Holland; we will explore their work later in this chapter.

Trait and factor theory posits that individuals’ career choices should be based on a thorough assessment of their traits, such as their abilities, interests, and values. In turn, these traits may be identified to match or align with suitable occupations within a person’s scope of interest. Parsons believed there was a strong connection between an individuals’ traits and success in one’s career, and he developed a three-step process for career decision making (Parsons, 1909).

Step 1. Self-Analysis: This step stresses the importance of self-assessment and reflection to understand your individual interests, abilities, and values. According to Parsons (1909), the first step when choosing a vocation is to determine the kind of work for which nature has best fitted you. In other words, individuals possess innate traits that significantly influence their career choices and serve as guiding factors in the vocational planning process. These inherent characteristics—which may include natural aptitudes, personality traits, and personal values—contribute to shaping an individual’s professional identity and determining the types of work environments and roles in which they are likely to succeed.

Step 2. Occupational Information: This step plays a critical role in the career decision-making process. Parsons (1909) emphasized that a key step in selecting a vocation involves understanding the nature of different occupations and the opportunities they present. He highlighted the importance of making informed career choices, a principle that remains relevant today. For both job seekers and career practitioners, researching various career options is often one of the initial steps in the career planning process. Parsons recognized that informed decision making and thorough evaluation are essential for enhancing job satisfaction and ensuring that individuals find meaningful and fulfilling opportunities in the workforce.

Step 3. Decision Making: Upon completion of the self-analysis and occupational review, “The third step is to choose from among the occupations for which you are fitted, those that seem most attractive” (Parsons, 1909, p. 91). In essence, Parsons suggests that the decision-making process allows an individual to make informed choices from gathered information and then evaluate the best career alignment. This process-oriented approach to career decision making certainly provides structure and guidance for job seekers which continues to this day. You will undoubtedly recognize similarities in their approach and may have discussed the value of assessment, evaluation, research, and importance of finding a strong “fit” in one’s career.

Limitations

When reflecting on my work over the past 30 years, there are tangible benefits for job seekers to engage in self-assessment and research to formulate the best decision possible in aligning an individuals interests, abilities, and goals toward a career. Without a doubt, this theory is practical and an important framework from which many career theoretical research is based upon, but at the same time, we must acknowledge there are limitations to this linear process-oriented approach. One consideration for job seekers is the oversimplification of this theory in our modern societal landscape. The world has changed dramatically since the early 1900s, and this theory is somewhat limited in considering cultural, global, and socioeconomic aspects of our society.

A strong argument can be made that Parsons did not account for barriers to employment arising from class, status, systemic racism, financial insecurity, and gender. Other limitations of this theory include how it does not take into account factors such as social influences, personal growth and development, life-long learning, and work-life balance. In modern society, job seekers are not looking for jobs that only align with their traits and abilities. Instead, there are a host of factors that enter into the decision making of an individual.

Holland’s Career Typology

One of the most influential traditional career theories that has been widely used for decades is Holland’s career typology, proposed by John Holland in the 1950s and refined over subsequent decades. Holland (1997) believed that, “Individuals seek out environments that complement their own personalities. People of the same personality type are likely to congregate in similar work environments.” From this, he surmised that individuals can be classified into six personality types: realistic, investigative, artistic, social, enterprising, and conventional (RIASEC).

Realistic individuals are described by their practical, hands-on approach to work and their preference for tangible, concrete tasks. These individuals are often referred to as “doers” because they thrive in environments where they can actively engage with tools, machines, equipment, and physical materials.

People with this personality type are often associated with hands-on occupations such as field work, construction, mechanical trades, industrial and natural resources, and labour intensive positions, but they also include occupations such as drafters, engineers, and pilots.

Investigative individuals tend to be analytical in nature and are described as curious individuals who enjoy solving complex problems. These individuals thrive in environments that challenge their thinking and allow them to explore, experiment, and uncover new knowledge. They are naturally drawn to roles that involve critical thinking, data analysis, and systematic inquiry, as they enjoy delving into the intricacies of how things work and finding innovative solutions to challenging questions. They are motivated by the opportunity to explore unanswered questions, develop new theories, or create practical solutions to real-world problems.

Under this typography, an individual may be suited for occupations in research, science, engineering, financial analysis, physics, and computer science.

Artistic individuals are often characterized by their creative nature and passion for self-expression. They are often drawn to roles that allow them to explore their artistic talents, think outside the box, and bring unique ideas to life. These individuals thrive in environments that encourage innovation, originality, and the freedom to express themselves, whether through visual, auditory, or written mediums. Artistic types are often found in professions that involve creating, designing, or performing. They are motivated by the opportunity to produce work that resonates with others, evokes emotion, or challenges conventional thinking.

This group’s occupations may be found in anything creative like music, acting, design, writing, photography, marketing, advertising, web design, and cinematography.

Social individuals are very engaging and tend to move toward positions that allow for social interaction, working with people, and supporting one another. Social types thrive in environments where they can engage with people, foster connections, and address the needs of individuals or groups. They are often found in professions that allow them to educate, heal, counsel, or advocate for others. For example, in teaching, they may excel at inspiring and nurturing students, while in social work, they might focus on empowering vulnerable populations and addressing systemic challenges. In counseling and therapy, their empathetic listening and problem-solving skills enable them to support individuals through personal struggles and mental health challenges.

Also known as helpers, this group often works in professions like teaching, social work, counselling, therapy, and community service.

Enterprising individuals are often characterized by their ambition, confidence, and natural inclination toward leadership. These individuals are driven by a desire to achieve, influence, and advance, often seeking out opportunities that allow them to take charge and make impactful decisions. They thrive in dynamic and competitive environments where they can exercise their persuasive communication skills, strategic thinking, and willingness to take calculated risks. Their ability to inspire and motivate others, combined with their goal-oriented mindset, makes them well-suited for roles that require vision, initiative, and the ability to navigate complex challenges.

This typography often gravitates towards positions in sales, business, entrepreneurship, management, and politics.

Conventional individuals, as described in Holland’s theory of vocational choice, are characterized by their detail-oriented, organized, and systematic approach to work. These individuals thrive in environments where precision, structure, and data-driven decision making are valued. They often exhibit a strong preference for tasks that involve working with numbers, statistics, and factual information, as they derive satisfaction from solving problems through logical and methodical processes. Their natural inclination toward order and efficiency makes them well-suited for roles that require accuracy, consistency, and adherence to established procedures.

Career alignment is often found in occupations in statistics, research, banking, accounting, data analysis, library sciences, and administration.

Limitations

Holland’s career typology has been a cornerstone for career counselling for many decades and has been used extensively to support job seekers with personalized guidance and recommendations for identifying suitable career paths. Individuals often display a blend of several personality types, with certain types exerting a stronger influence than others. This combination of traits reflects the complexity and diversity of human personalities, as people rarely fit neatly into a single category. So, while Holland’s typology certainly serves as a valuable framework for understanding career preferences and decision making, it is not without limitations due to the sheer complexity of human beings. Notably, it overlooks critical contextual elements such as human diversity, cultural background, personal values, and skill sets, all of which contribute to the multifaceted nature of career development. This very complexity is what makes career decision making both fascinating and, at times, challenging, as there is rarely a clear or straightforward pathway to follow. The interplay of personal, cultural, and contextual factors adds layers of nuance that theoretical models alone cannot fully capture.

Super’s Life-Span Theory

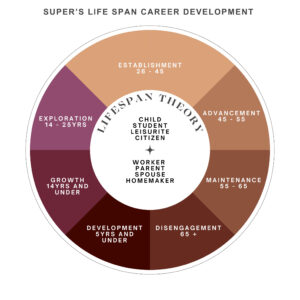

Another prominent career theory is Donald Super’s (1957, 1980) life-span, life-space theory, developed in the 1950s and 1960s. Super’s theory emphasizes the importance of individual development and the role of various life roles (e.g., student, worker, family member) in shaping one’s career trajectory. Donald Super’s (1990) theory highlights that individuals undergo a continuous process of personal and professional development across their lifespan. This process is characterized by a series of interconnected challenges, opportunities, and milestones that arise as individuals grow and evolve. These developmental tasks are not isolated incidents but are deeply intertwined, collectively shaping a person’s identity, aspirations, and sense of purpose over time. Super’s framework underscores the dynamic and evolving nature of career development, emphasizing how each stage of life contributes to the ongoing construction of an individual’s personal and professional narrative.

Super (1980) conceptualized career development as a series of overlapping and interconnected stages of growth, exploration, establishment, maintenance, and disengagement to illustrate the dynamic and evolving nature of career trajectories over the lifespan. These stages reflect the continuous process through which individuals navigate their personal and professional lives, and for the purposes of the revised graphic, the establishment stage has been expanded to provide a more nuanced understanding of this critical phase, which involves not only stabilizing one’s career but also achieving professional growth and recognition. Additionally, a new stage, advancement, has been introduced to better capture the period during which individuals seek to refine their expertise, assume leadership roles, and make significant contributions to their fields. This expansion acknowledges the complexity of modern career paths and the increasing importance of ongoing development and reinvention in response to evolving workplace demands and personal goals. By incorporating these refinements, the revised framework offers a more comprehensive representation of the multifaceted and non-linear nature of career development, aligning with contemporary understandings of lifelong learning and professional growth.

Super (1957, 1980) initially split a person’s life into five stages, but this has been adapted slightly to include another stage:

Development and Growth Stage (0–14 years of age): During this formative stage individuals are forming their identity and a sense of who they are. This self-discovery often lead to development of interests and the formation of relationships and bonds. Super (1957, 1980) posited that even in this early stage, individuals lay the foundation for future career development by fostering curiosity, creativity, and the initial formation of self-concept. Children start to imagine potential roles and careers, often influenced by family, school, and societal expectations.

Exploratory Stage (14–25 years of age): As individuals progress through adolescence and into early adulthood, they continue to experience growth and exploration. This stage is marked by the pursuit of various interests, development of skills and knowledge, and active engagement in the career exploration and decision-making processes. Super (1980) emphasized that this period involves significant trial and error, as individuals seek to align their interests, abilities, and values with potential career paths. Key tasks include career planning, skill development, and decision making, often culminating in the transition from education to the workforce. During this stage, we often witness individuals trying different occupations figuring out what they like and do not like to do.

Establishment Stage (25–45 years of age): This stage is exemplified by individuals concentrating on reaching career objectives, refining skills, and progressing in selected professions. This phase is marked by the quest for professional acknowledgement and career development. Individuals are focused on building, stabilizing, and establishing themselves in their chosen fields so they may advance professionally. Super (1980) noted that this stage often involves overcoming challenges, such as adapting to workplace dynamics, achieving work-life balance, and refining career goals. Success during this stage is marked by career growth, increased responsibility, and a sense of contribution to one’s field.

Advancement Stage (45-55 years of age): While absent in Super’s initial life-span theory, this stage is represents a critical phase in the career development that builds upon the establishment stage and reflects the evolving demands of modern professional roles. This stage typically occurs during mid-career, when individuals have already gained a foothold in their chosen field and are now focused on achieving higher levels of expertise, influence, and leadership. Unlike the establishment stage, which emphasizes stability and consolidation, the advancement stage is characterized by proactive efforts to refine skills, expand responsibilities, and make meaningful contributions to one’s profession or organization. Advancement can certainly occur at an stage, but it is particularly significant during one’s mid to late career, when individuals have accumulated substantial experience and are positioned to take on greater responsibilities, leadership roles, and innovative challenges.

Maintenance Stage (45–64 years of age): Characteristics of this stage include stability and achievement in your career, with a focus of transitioning into retirement in the latter part of this stage. During the maintenance stage, individuals strive to preserve their career achievements and adapt to changing circumstances. This stage involves updating skills, mentoring others, and navigating transitions, such as organizational changes or shifts in personal priorities. Super (1980) highlighted that individuals in this stage may also reassess their career satisfaction and explore new opportunities for growth or reinvention, reflecting the ongoing nature of career development.

Disengagement Stage (65+ years of age): The final stage involves a gradual withdrawal from the workforce and a transition into retirement or reduced work involvement. Super (1980) described this stage as a time for reflection, legacy-building, and redefining one’s identity beyond professional roles. Individuals may focus on leisure activities, volunteer work, or mentoring, while also adjusting to the psychological and social changes associated with retirement. For many individuals, this stage provides opportunities for legacy building, increased flexibility, and reducing day-to-day stress of the position. For others, this stage represents the significant challenges of social isolation and loss of identity and purpose.

Limitations

Upon first glance, Super’s lifecycle provides a neat and tidy linear approach to understanding the career development process, but it is clear these transitory stages are a guide to explain the human experience. Individuals are highly complex, and Super acknowledges that career choice is a lifelong journey influenced by many factors. It is expected that we would move through these stages at different intervals, and how we navigate these cycles is highly dependent on factors such as family support, environmental factors, culture, technology, and geography. Super (1980) stated, “Career development is the total constellation of economic, sociological, psychological, educational, physical and chance factors that combine to shape one’s career. It occurs throughout one’s life and includes home, school, community, and workplace.”

To Super’s credit, he recognized the complexity of the human condition and how personal career development is from one individual to another. He understood that life-span theory could not account for every impact and change we face in our daily lives, but by acknowledging these limitations, we can still gain insight on how to navigate our career journey.

Social Cognitive Career Theory

Social cognitive career theory (SCCT), spearheaded by scholars Robert Lent, Steven Brown, and Gail Hackett (1994, 1996), emerged in the 1990s as a significant advancement in the field of career development. Influenced by Bandura’s (1997) social cognitive theory, SCCT examines psychological principles and constructs to decode the process that individuals use when initiating career decision making. At its core, SCCT seeks to unveil the underlying factors that influence an individual’s engagement and deliberations in career exploration and decision making. The central tenets of SCCT are a confluence of factors to explain how individuals develop interests in a certain career and how they navigate this process. SCCT defines these factors that shape an individual’s career choices and behaviours as phases that include self-efficacy beliefs, outcome expectations, social influences, and personal goals.

Self-Efficacy

According to SCCT, individuals develop self-efficacy beliefs regarding their abilities to perform specific tasks or succeed in particular careers. These beliefs, in turn, may influence career interests, goals, and actions. Lent et al. (1994) proposed that an individual’s self-efficacy beliefs influence their motivation, persistence, and performance in career-related activities.

For example, if an individual believes they have the aptitude or capabilities to perform certain tasks, then they may gravitate towards certain occupations that provide these opportunities. To drill down further, if an individual has an affinity for numbers and solving problems, SCCT posits that the individual may have a belief they may be suited for occupations within accounting, statistics, and finance. Similarly, if an individual has strong spatial skills, they may develop high self-efficacy for careers that require visualization, design, and spatial reasoning, such as architecture, engineering, or graphic design. Their confidence in these abilities, reinforced by successful experiences or encouragement from others, can lead them to pursue educational and career paths that align with these strengths. Over time, this self-efficacy can influence their career interests, goals, and performance, ultimately shaping their professional trajectory.

What is interesting about self-efficacy is that ones goals are not fixed or set in stone. They can be influenced by role models, experiences in work-integrated learning environments (e.g., co-op, mentors), and other positive factors in one’s life.

Performance Outcomes

The performance outcomes phase involves an individual’s positive outcome expectations and belief that they can be successful in their career actions. Lent et al. (1996) proposed that an individual’s career choices and performance behaviours are influenced by their interests, goals, self-efficacy beliefs, and outcome expectations; so if an individual believes they will have a positive outcome, then they will be motivated to pursue their stated goals, no matter how ambitious they may be. Positive outcome expectations refer to an individual’s belief that their efforts will lead to desirable results, while self-efficacy beliefs reflect an individual’s confidence in their ability to perform the tasks necessary to achieve those outcomes.

From a student’s work-integrated learning perspective, we often see a student’s belief that their efforts during the co-op will lead to desirable results, such as skill development, networking opportunities, or future job offers. If a student believes that their co-op experience will contribute to their long-term career success, they are more likely to approach the experience with enthusiasm and commitment.

Interests & Goals

The interests and goals phase involves the formation of an individual’s career-related interests and goals. SCCT suggests that individuals develop interests and goals based on their personal characteristics, experiences, and social influences. Lent et al. (1994) emphasized how this phase connects with the role of self-efficacy beliefs and outcome expectations to shape an individual’s interests and goals. From a student perspective, a co-op experience allows students to explore their career interests in a practical setting. SCCT suggests that interests play a key role in guiding career-related behaviours. If a student’s co-op aligns with their interests, they are more likely to engage deeply with their work, seek out additional responsibilities, and consider pursuing similar roles in the future.

For example, a student passionate about environmental sustainability may thrive in a co-op role at a renewable energy company, while a student with little interest in the field may struggle to stay motivated. Co-op experiences can help students clarify their interests by exposing them to different industries, roles, and work environments, enabling them to make more informed career decisions.

Environmental & Social Factors

Another interesting aspect of SCCT is the importance of social and environmental in shaping an individual’s career aspirations and outcomes. These positive influences greatly enhance an individual’s belief that they can accomplish their stated goals and objectives. Lent et al. (1994) emphasized the importance of contextual supports in facilitating or hindering an individual’s career choices and behaviours. Contextual supports include social support, mentoring, access to resources, and opportunities for skill development.

In work-integrated learning environments, such as co-op placements, internships, or practicums, the impact of these contextual supports is particularly evident. We as faculty and career educators have witnessed time and time again how students thrive when they are provided with strong mentorship, access to resources, and a supportive network. For example, a student participating in a co-op program may benefit from a supervisor who provides guidance, constructive feedback, and encouragement, thereby boosting their confidence and self-efficacy. Similarly, access to resources such as professional development workshops or networking events can help students build essential skills and expand their career opportunities.

Social support from peers and family also plays a vital role in shaping students’ career aspirations and persistence. Encouragement from loved ones can motivate students to pursue ambitious goals, while peer support can create a sense of camaraderie and shared purpose. In contrast, a lack of contextual supports—such as limited access to mentors, resources, or encouragement—can hinder a student’s ability to fully engage in their work-integrated learning experience and achieve their potential.

Limitations

SCCT certainly adds to career theory research by providing a comprehensive framework that integrates psychological principles to further refine the career development process; however, there are also challenges that should be acknowledged. The theory itself is quite complex and requires a deep understanding of factors that may contribute to decision making. As well, the focus on self-efficacy and personal goals may overshadow the significance of social and economic conditions. With the increasing globalization of the workforce, there is also the potential to overlook the importance of cultural considerations that address diverse cultural norms and expectations. In summary, there is certainly value to this theory, but as our society continues to evolve, individuals may need to complement this framework with additional perspectives to provide a holistic approach to career decision making.

Timeline of Career Theory

If you are using a printed copy, you can scan the QR code with your digital device to go directly to Timeline of Career Theory

Evolving Career Theory Perspectives

In response to the swift transformations in society, conventional career theories found themselves struggling to fully grasp the intricate dynamics of contemporary work settings. The impact of globalization, rapid technological progress, and evolving socioeconomic conditions emphasized the need for more fluid and responsive models in career development. Consequently, there was a proliferation of fresh paradigms, the most prominent being planned happenstance and chaos theory.

The concepts behind planned happenstance and chaos theory provide fresh perspectives and strategic guidance for individuals in the present era who are confronted with navigating an ever-changing and unpredictable job market. Planned happenstance advocates for being open to unplanned opportunities and unanticipated events, viewing them not as obstacles but as potential avenues for growth and career advancement. On the other hand, chaos theory underscores the idea that even seemingly random or chaotic events in one’s career trajectory may reveal underlying patterns and opportunities for adaptation and progress. By embracing the principles of these theories, individuals can better equip themselves to thrive in today’s dynamic professional landscape by fostering a mindset of resilience, flexibility, and strategic adaptation.

Planned Happenstance Theory

Developed by Kathleen Mitchell, S. Al Levin, and John Krumboltz (1999), planned happenstance is a theory that challenges the traditional notions of carefully planned career paths. It suggests that unplanned events and chance encounters play a significant role in shaping one’s career trajectory. Krumboltz’s (1979) social learning theory of career decision making forms the basis for planned happenstance, emphasizing the importance of learning experiences, social influences, and happenstance events.

Planned happenstance theory introduces several key principles that contribute to a more nuanced understanding of career development (Mitchell et al., 1999), including:

- Planned Happenstance: Krumboltz and Levin (2004) argue that individuals can proactively create opportunities by developing skills in curiosity, persistence, flexibility, and optimism. By embracing uncertainty and being open to unexpected events, individuals can turn chance occurrences into positive career developments.

- Learning from Unplanned Events: This theory posits that individuals can learn valuable lessons from unplanned events and use these experiences to refine their career goals. This adaptive learning process involves making sense of unexpected situations and integrating them into one’s career narrative.

- Social Networks and Support: Planned happenstance emphasizes the role of social networks in creating and capitalizing on unplanned opportunities. Strong social connections provide access to diverse information, resources, and support, enhancing an individual’s ability to navigate the unpredictable nature of the job market.

Practical Applications

Planned happenstance has many practical implications for individuals who are navigating their careers. It is important to note that while planning and goal setting are still an important part of the career planning process, one should never underestimate the importance of being flexible, being open to unplanned opportunities and events, being curious, and recognizing unplanned social factors that are out of your control but may greatly impact your career planning.

A fairly recent example of unplanned social factors would be the COVID-19 pandemic that affected the entire planet in 2020 and 2021. There was no way that one could plan for such a catastrophic global event, and we are still feeling the effects of supply-chain challenges and rampant inflation in the economy. As we move further into this decade, we anticipate these factors to be less acute, but there is no denying that we are in a new reality of how and where we work.

For instance, the job market has changed dramatically since the COVID-19 pandemic. By embracing planned happenstance, individuals were quick to recognize opportunities in an environment of monumental change. Adopting a flexible mindset, individual and industries quickly pivoted from Plan A to Plan B methods that were resilient to the pandemic. The emergence of the digital nomad and remote or virtual worker were historically more niche in scope, but during the pandemic, these “ideals” were embraced and, quite frankly, necessary to keep the economies of the world functioning. The awareness of individuals pivoting in such a manner is remarkable in the history of modern labour and a testament to how quickly economies may change.

Of course, the COVID-19 pandemic is just one example we can draw from. The digital transformation that the pandemic spawned is now leading humanity to embrace digital tools, such as artificial intelligence (AI). AI will bring enduring innovation and fundamentally change our economies as we have traditionally known them, but these technologies will also bring massive opportunities that we may or may not be currently aware of.

Key Concepts

If job seekers embrace the notion that chance events and unexpected opportunities can play a role in one’s career trajectory, then planned happenstance as a theory may resonate with individuals who are navigating these turbulent economic waters. In the list below, we have identified key elements to further understand the value of planned happenstance:

- Embrace Uncertainty: We are in a rapid state of economic change, and one could argue this is the greatest period of uncertainty and disruptive forces we have faced in decades. Developing a mindset that embraces uncertainty and encourages proactive engagement with unexpected events will foster adaptability and resilience, thus helping individuals to better navigate the complexities of the modern job market.

- Skill Development: Planned happenstance highlights the importance of developing skills such as adaptability, networking, and problem solving. These skills not only enhance an individual’s employability but also empower them to capitalize on unforeseen opportunities and emerging career paths. Technological advancements and economic fluctuations will require skills that we have not even anticipated.

- Flexibility and Adaptability: Krumboltz (2009) emphasizes the importance of adaptability and flexibility in career decision making and suggests that individuals should be open to exploring various career options and adapting their goals based on changing circumstances and personal experiences.

- Social Connections and Networking: Networking plays a crucial role in planned happenstance theory by actively engaging in professional networks, attending events, and building connections. Job seekers increase their chances of creating unforeseen opportunities through these actions, and these chance encounters can lead to mentorships, job offers, referrals, or valuable insights into potential career paths.

- Lifelong learning and Personal Growth: In such a dynamic job market, planned happenstance theory can lead an individual on a journey the encourages continuous growth, learning, and development. Through these actions, individuals are typically exposed to new challenges and opportunities that may lead to unexpected opportunities.

- Chance and Awareness: Being aware of how important “chance” encounters are leads to new prospects and career pathways that may lead individuals in career directions they had not thought possible.

In summary, flexibility, chance, and embracing uncertainty are the cornerstones of planned happenstance theory, which empowers job seekers to manage their careers by recognizing that career paths are rarely linear. Instead of following a rigid job search plan, individuals should remain open to unexpected opportunities and chance encounters that may lead to new career paths or advancements. Ultimately, this theory posits that a linear approach is too rigid in our complex world, and individuals who embrace the notion of adaptability, resilience, flexibility, and openness will actively create conditions that increase the likelihood of career opportunities and success.

Chaos Theory of Careers

The inspiration for the chaos theory of careers (CTC) finds its origins in mathematics and physics. Edward Lorenz’s (1963) work on “deterministic nonperiodic flow” is often considered the starting point of chaos theory. Over time, the work of Robert May (1976), Benoit Mandelbrot (1977), and Edward Lorenz (1963) continued to build on this work by exploring the unpredictable and non-linear dynamics of complex systems. These principles have been adopted and applied to various fields, including CTC.

As highlighted earlier in this chapter, the job market and influences that affect labour and global economies continue to evolve at a rapid pace. Traditional linear career theories often fall short in capturing these complexities that we all face in our professional lives, but similar to planned happenstance theory, CTC has emerged as a dynamic theory framework that embraces the unpredictable and non-linear nature of career development. Developed by Dr. Jim Bright and Dr. Rober Pryor (2005), CTC challenges traditional linear thinking theories of career planning and offers a more nuanced modern approach that recognizes the chaos and turbulence in the job environment.

When applied to career development, CTC challenges some assumptions of traditional career theories and suggests that individuals’ career paths are inherently unpredictable, influenced by chance events, personal agency, and interactions between one’s career environment and internal characteristics.

Watch the following video by Jim Bright to learn about the foundations of chaos theory.

The Chaos Theory of Careers – its about complexity! [7:49 min] by Jim Bright (2015)

If you are using a printed copy, you can scan the QR code with your digital device to go directly to the video: The Chaos Theory of Careers – its about complexity!

Avalanche-Snowflake Metaphor

The relationship between avalanches and snowflakes (Bright & Pryor, 2005) is another metaphor that is often used to illustrate how large and transformative changes (avalanches) can stem from small, seemingly insignificant actions (snowflakes). It underscores the idea that significant career developments can emerge from minor decisions, interactions, or events.

In this metaphor, snowflakes represent the small, everyday decisions, interactions, or events that may appear inconsequential at the time. For example, attending a networking event, taking an elective course, or having a casual conversation with a colleague can all be considered “snowflakes.” Individually, these actions may seem minor, but they have the potential to set off a chain reaction that leads to significant outcomes.

Avalanches symbolize the large, transformative changes that can result from the accumulation of snowflakes. In a career context, an avalanche might represent a major career shift, such as landing a dream job, starting a business, or transitioning to a new industry. These changes often feel sudden or unexpected, but they are the result of a series of small, interconnected actions and events.

From a student perspective this metaphor is particularly powerful, because small, intentional actions can lead to significant outcomes over time. Consistently building professional relationships, pursuing learning opportunities, or exploring new interests can create a foundation for future opportunities. While the immediate impact of these actions may not be apparent at first, they contribute to the conditions that make transformative change possible.

The avalanche-snowflake metaphor also illustrates how career development is shaped by a complex web of interconnected factors. A single decision or event can have ripple effects that influence multiple aspects of an individual’s career. For instance, accepting a temporary job in a new field, joining a student club, or becoming a co-op student or ambassador might lead to unexpected skills, connections, and opportunities that open doors to a completely different career path.

Finally, this metaphor encourages individuals to embrace uncertainty and remain adaptable in their career journeys. Just as an avalanche cannot be precisely predicted or controlled, career paths are often shaped by unforeseen events and opportunities. By staying open to change and proactively engaging with small actions, individuals can position themselves to capitalize on transformative moments when they arise.

Key Concepts & Implications

Below, we have identified key elements of chaos theory to further understand its value:

- Navigating Uncertainty: Chaos theory suggests that complex systems, such as the job market, are highly sensitive to initial conditions and inherently unpredictable. Job seekers can apply chaos theory principles by acknowledging the unpredictability of the job market and adopting flexible strategies to navigate uncertainty. Rather than striving for rigid control or linear progression, individuals are encouraged to embrace ambiguity and navigate their careers with a sense of curiosity, adaptability, and resilience. CTC encourages individuals to embrace the inherent uncertainty in their careers.

Navigating Uncertainty Example

- Flexibility and Resilience: The non-linear and unpredictable nature of career development underscores the importance of flexibility and resilience. Individuals who can adapt to changing circumstances and bounce back from setbacks are better equipped to navigate the complex and dynamic job market.

Flexibility & Resilience Example

- Recognizing Chance Events: The concept of “avalanches” emphasizes the role of chance events or critical moments in shaping career outcomes. Understanding that career paths can be influenced by unexpected opportunities or challenges encourages individuals to remain open to serendipitous encounters and capitalize on them when they arise.

Recognizing Chance Events Example

- Valuing Incremental Progress: Conversely, “snowflakes” represent the cumulative impact of small, incremental changes or experiences over time. This highlights the importance of patience and persistence in career development, recognizing that even seemingly minor actions or decisions can contribute to long-term success.

Valuing Incremental Progress Example

- Exploring Diverse Opportunities: Chaos theory encourages job seekers to explore diverse opportunities and consider alternative paths. Instead of focusing solely on traditional job listings, they can explore freelance work, project-based opportunities, remote positions, or entrepreneurial ventures. By embracing a diverse range of opportunities, job seekers can leverage the non-linear nature of the job market and uncover unexpected avenues for career growth.

CTC Summary

If you are using a printed copy, you can scan the QR code with your digital device to go directly to CTC Summary

Integration & Adoption of Planned Happenstance & Chaos Theory

As reviewed in this chapter, planned happenstance theory emphasizes the role of chance and unplanned events in shaping an individual’s career, while the chaos theory of careers explores the chaotic and unpredictable nature of career paths. While planned happenstance and chaos theory have distinct foundations, they share a common ground in challenging deterministic and linear views of career development. Both perspectives acknowledge the importance of unplanned events, adaptability, and the dynamic interplay of unforeseen opportunities in shaping careers. Rather than viewing uncertainty as a barrier, planned happenstance and chaos theory embrace it as a natural part of the career development process. The combined insights from these theories provide individuals with a more robust toolkit for navigating uncertainty.

By applying principles from both theories, individuals can proactively seek out diverse opportunities, network with professionals from different fields, and adapt to changing market demands to effectively navigate uncertainty.

Case Studies

To illustrate the practical applications of planned happenstance and chaos theory, this chapter includes case studies of individuals who have successfully navigated their careers by embracing career theory.

Case Study 1.1

Fiona’s Career Journey: Embracing Planned Happenstance

Fiona, a recent graduate with a degree in marketing, initially had a clear career path in mind. She aimed to secure a position at a top advertising agency in her city. However, despite her diligent job search efforts, she struggled to land a job in her desired field.

Instead of becoming discouraged, Fiona decided to attend networking events, volunteered for projects outside her comfort zone, and actively sought informational interviews with professionals in various industries. During one such interview, she met a marketing executive who mentioned an upcoming internship opportunity at a tech start-up.

Although Fiona had never considered working in the tech industry, she decided to seize the opportunity. The internship exposed her to new skills, challenges, and perspectives. She discovered a passion for digital marketing and data analytics, areas she had not explored during her academic studies.

As Fiona immersed herself in the tech startup environment, she encountered unexpected opportunities for growth and advancement. She leveraged her newfound skills to contribute meaningfully to the company’s marketing initiatives, eventually securing a full-time position as a digital marketing specialist.

Case Study 1.1

Discussion Questions

If you are using a printed copy, you can scan the QR code with your digital device to go directly to Case Study 1.1 Discussion Questions A

If you are using a printed copy, you can scan the QR code with your digital device to go directly to Case Study 1.1 Discussion Questions B

Case Study 1.2

Jose’s Career Evolution: Embracing Chaos Theory

Jose is a university student approaching graduation with a degree in business administration. He is feeling uncertain and overwhelmed about his future career path. Jose is interested in various fields—including marketing, finance, and entrepreneurship—but struggles to narrow down his options. He is finding it challenging and overwhelming to pinpoint a specific career path, and he is worried he will not be able to find the perfect career.

As Jose delves deeper into his career exploration, he reaches a point where he must make decisions that will shape his future path. He recognizes the need to narrow down his options and focus on areas that align with his skills, interests, and values. At this critical juncture, Jose starts to feel the pressure of making a definitive choice amidst the uncertainty and complexity of his decision-making process.

Case Study 1.2

Discussion Questions

Utilizing the chaos theory of careers, what steps could Jose take to navigate his career decision-making process?

Questions to Consider:

- How did Jose leverage the chaos theory for careers to navigate his decision-making process?

- What challenges did Jose face at each phase of his career exploration, and how did he overcome them?

- How did Jose’s interdisciplinary interests in marketing, finance, and entrepreneurship shape his career trajectory?

- What lessons can students draw from Jose’s experience in embracing chaos and complexity in career decision-making?

- How can students apply the principles of the chaos theory for careers to their own career planning and exploration processes?

Discussion Questions

If you are using a printed copy, you can scan the QR code with your digital device to go directly to Case Study 1.2 Discussion Questions

Conclusion

Delving into career theory offers insights into the intricate and ever-evolving landscape of career growth. Throughout this chapter, we explored a range of career theories that provide frameworks for understanding individual career trajectories, decision-making processes, and the broader socioeconomic contexts that influence career development. Ranging from conventional theories—such as trait and factor theory and developmental theory—to modern perspectives—like social cognitive career theory, planned happenstance theory, and the chaos theory of careers—each theory bestows distinctive viewpoints that enrich our comprehension of career advancement.

A pivotal takeaway from our exploration is the recognition that a universal one-size-fits-all approach to career development is impractical. Scholars like Super (1980, 1990) underscore that a singular theory lacks the breadth to entirely explain the multifaceted career decision making processes given individuals’ unique traits, diverse interests, values, strengths, and environmental circumstances that shape their career journeys in distinct ways. Instead, we recognize the need for a convergence of theories to make meaning of the themes, principles, and concepts shared across different frameworks (Savickas & Lent, 1994).

Career theories serve as indispensable resources and frameworks for individuals to navigate the complexities of career development and support a more informed pathway. As societal dynamics evolve, career theories will continuously adapt to a myriad of factors that influence all of us in the choices we make. Individual characteristics, social influences, environmental factors, and the interplay between personal agency and external constraints will continue to evolve, and the evolution of career theory will reflect broader societal changes and shifts in our world. Traditional linear models of career development have given way to more dynamic and non-linear approaches, and as we move forward, it is essential to continue refining and expanding our understanding of career development through interdisciplinary research, empirical studies, and practical applications. By integrating insights from psychology, sociology, economics, and other relevant fields, we can develop more holistic approaches to career theory that address the diverse needs and aspirations of individuals across different stages of their careers and lives.

In conclusion, career theory serves as a valuable foundation for understanding, guiding, and supporting individuals in their career journeys. By applying insights from the highlighted theories in this chapter, you will be empowered to make informed decisions to pursue meaningful and fulfilling careers in an ever-changing world.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1.1 “Career theory word cloud”[created using Canva] by the author is used under the Canva Content License.

- Figure 1.2 “Parson’s trait theory of career development” [created using Canva] by the author is used under the Canva Content License.

- Figure 1.3 “Word Unrealistic turned into Realistic” by pepifoto (n.d.), via Canva, is used under the Canva Content License.

- Figure 1.4 “Investigative personality type” [created using Canva] by the author [original image by apodiam] is used under the Canva Content License.

- Figure 1.5 “Artistic personality type” [created using Canva] by the author [original image by Ivan Pantic] is used under the Canva Content License.

- Figure 1.6 “Social personality type” [created using Canva] by the author [original image by pixelfit] is used under the Canva Content License.

- Figure 1.7 “Enterprise 2.0” by vaeenma (n.d.), via Canva, is used under the Canva Content License.

- Figure 1.8 “Convention” by Warchi (n.d.), via Canva, is used under the Canva Content License.

- Figure 1.9 “Super’s life span career development” [created using Canva; based on D. E. Super’s (1980) “A Life-Span, Life-Space Approach to Career Development”] by the author is used under the Canva Content License.

- Figure 1.10 “Social cognitive career theory” [created using Canva] by the author is used under the Canva Content License.

- Figure 1.11 “Planned happenstance theory” [created using Canva] by the author is used under the Canva Content License.

- Figure 1.12 “Businessman hand flipping wooden cube blocks with PLAN A change to PLAN B text on table background. strategy, analysis, marketing, project and Crisis concepts” by Panuwat Dangsungnoen (n.d.), via Canva, is used under the Canva Content License.

- Figure 1.13 “Chance To Change” by Philip Steury (n.d.), via Canva, is used under the Canva Content License.

- Figure 1.14 “Chaos theory of careers” [created using Canva] by the author is used under the Canva Content License.

- Figure 1.15 “Key concepts of the chaos theory of careers” [created using Canva] by the author is used under the Canva Content License.

References

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman and Company.

Bright, J. E. H. & Pryor, R. G. L. (2005). The chaos theory of careers: A user’s guide. The Career Development Quarterly, 53(4), 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2005.tb00660.x

Bright, J. E. H. & Pryor, R. G. L. (2008). Shiftwork: A Chaos Theory Of Careers agenda for change in career counselling. Australian Journal of Career Development. 17(3), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/103841620801700309

Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments (3rd ed.). Psychological Assessment Resources.

Jena, L., & Nayak, U. (2020). Theories of career development: An analysis. Indian Journal of Natural Sciences, 10(60), 23515–23523.

Jim Bright. (2015, October 14). The chaos theory of careers – its about complexity! [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/AVGA1cQX4D4?si=n6YOSEf3CIBZnBdz

Krumboltz, J. D. (1979). A social learning theory of career selection. The Counseling Psychologist, 6(1), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/001100007600600117

Krumboltz, J. D. (1994). Improving career development theory from a social learning perspective. In R. Lent & M. Savickas (Eds.), Convergence in career development theories: Implications for science and practice (pp. 9-31). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Krumboltz, J. D., & Levin, A. S. (2004). Luck is no accident: Making the most of happenstance in your life and career. Atascadero, CA: Impact Publishers.

Krumboltz, J. D. (2009). The happenstance learning theory. Journal of Career Assessment, 17, 135–154. doi:10.11771069072708328861.

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45(1), 79–122. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1996). Career development from a social cognitive perspective. In D. Brown, L. Brooks, & Associates (Eds.), Career choice and development (3rd ed., pp. 373–421). Jossey-Bass.

Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2002). Social cognitive career theory and adult career development. In S. G. Niles (Ed.), Adult career development: Concepts, issues and practices (3rd ed., pp. 76–97). National Career Development Association.

Lorenz, E. N. (1963). Deterministic nonperiodic flow. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 20(2), 130–141. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1963)020<0130:DNF>2.0.CO;2

Mandelbrot, B. B. (1977). Fractals: Form, chance, and dimension. W. H. Freeman and Company.

May, R. M. (1976). Simple mathematical models with very complicated dynamics. Nature, 261, 459–467. https://doi.org/10.1038/261459a0

McMahon, M., & Patton, W. (1995). Development of a systems theory of career development: A brief overview. Australian Journal of Career Development, 4(2), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/103841629500400207

Mitchell, K. E., Levin, A. S., & Krumboltz, J. D. (1999). Planned happenstance: Constructing unexpected career opportunities. Journal of Counseling & Development, 77(2), 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1999.tb02431.x

Parsons, F. (1909). Choosing a vocation. Houghton, Mifflin and Company.

Patton, W., & McMahon, M (2006). The systems theory framework of career development and counseling: Connecting theory and practice. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 28(2), 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-005-9010-1

Savickas M. L., Lent R. W. (1994). Convergence in career development theories: Implications for Science and Practice. Consulting Psychologists Press.

Sharma, P. (2016). Theories of career development: Education and counseling implication. The Internationl Journal of Indian Psychology, 3(4). https://doi.org/10.25215/0304.116

Super, D. E. (1957). The psychology of careers: An introduction to vocational development. Harper & Row.

Super, D. E. (1980). A life-span, life-space approach to career development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 16(3), 282–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(80)90056-1

Super, D. E. (1990). A life-span, life-space approach to career development. In D. Brown, L. Brooks, & Associates (Eds.), Career choice and development: Applying contemporary theories to practice (2nd ed., pp. 197–261). Jossey-Bass.

TEDx Talks. (2018, May 7). The psychology of career decisions | Sharon Belden Castonguay | TEDxWesleyanU [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/4e6KSaCxcHs?si=_pJAIToHTJoKI_hr

Long Descriptions

Figure 1.1 Long Description: Words related to career theory include: accept, adjust, alternative, assessment, attending, butterfly, career, chance, change, changes, chaos, complexity, confidence, constructivism, decision, developmental, diverse, economic, effect, embracing, encounters, entrepreneurial, events, evolving, flexibility, freelance, Ginzberg, happenstance, Holland, influences, integrated, interconnectedness, know, learning, life, lifelong, making, market, minded, navigating, networking, networks, open, opportunities, Parsons, paths, personality, perspectives, planned, planning, positions, professional, project-based, remote, resilience, risks, search, seeker, self, social, span, strategies, strengths, success, Super, theory, trait, uncertainty, unexpected, unpredictable, ventures, weaknesses, work, and cognitive. [Return to Figure 1.1]

- Title: Super’s Life Span Career Development

- Inner circle: Lifespan Theory (at the top) — child, student, leisure, citizen (above a star) — worker, parent, spouse, homemaker (below the star)

- Outer circle: Development 5 years and under, Growth 14 years and under, Exploration 14–25 years, Establishment 26–45, Advancement 45–55, Maintenance 55–65, Disengagement 65+